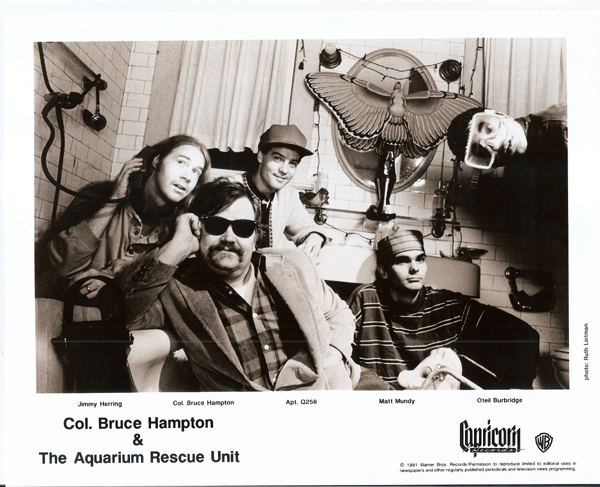

Col. Bruce Hampton and the ARU: An Appreciation

Early ARU photo – note pre-beard Jimmy Herring!

This story originally ran in Relix’ 40th Anniversary Issue.

In February 1992, the reunited Dixie Dregs were coming to New York’s Ritz and I was excited to check them out. Though I had always considered their music sterile if brilliantly constructed, I recognized Steve Morse as a brilliant guitarist. As a young Guitar World Managing Editor, I was anxious to expand my musical scope and appreciation and Steve was someone that I thought I should better understand. Publicist Marc Pucci pushed me to get there early to see the opening act, the oddly named Aquarium Rescue Unit

He assured me that the newly reformed Capricorn Records was very excited about the band, led by a longtime Atlanta cult hero, Col. Bruce Hampton (Ret.). Still pinching myself over living in New York City, working at a major music magazine and having publicists ask me to go to shows, I earnestly arrived at the Ritz close to starting time to check out this band with an open mind but with few expectations. They had just started when I walked in to the half-filed Midtown Manhattan ballroom and strolled right up to the lip of the stage, immediately astounded by what was unfolded.

A skinny redheaded guy with a beard was hunched over a Stratocaster, dispensing lightning fast licks that danced the razor’s edge I love, where everything could fall apart at any moment, though his sure-handed playing and obvious blues rooting made that highly unlikely. To his right, a handsome young man was grinning, eyes cast towards the sky as he worked a six-string bass with the same mix of skill and abandon, sometimes scatting along to the notes he played. On the other side of the stage a dark haired guy with bushy eyebrows was blasting out supercharged bluegrass licks on a Mandocaster – a mandolin in the shape of a mini Telecaster. A brilliant drummer was laying down beats from enough angles to replicate at least two percussionists. Overseeing the whole thing was a crazy little man with a handlebar moustache playing some kind of demented short-scale instrument I would later learn he called a Chazoid. He sang like a bastard child of Bobby Bland and Hazel Dickens and occasionally played wicked, inspired licks. This was obviously the Colonel. He was clearly the ringmaster of this nutty circus, which radiated light and the spark of life and was hilarious without being a joke.

Questions bounced around my racing mind: Who was he? What was this? Why wasn’t everyone talking about this fabulous band? I pushed them all down and out because I wanted to stay in the moment, to drink deeply from this heady brew. I’d like to tell you how the rest of the crowd reacted, but I have no idea. I wasn’t looking around, solely focused on the stage, experiencing something that I have just a handful of times – musical nirvana that hit me in the head, heart and guts at the same time and was all the more powerful for being so completely unexpected.

After the show, I watched the musicians break down their own gear and got guitarist Jimmy Herring’s attention, introducing myself and telling him I’d meet him downstairs. I had been invited to a meet and greet, which I had originally planned on stopping by just long enough to see whether or not they had free beer, but my plans had changed.

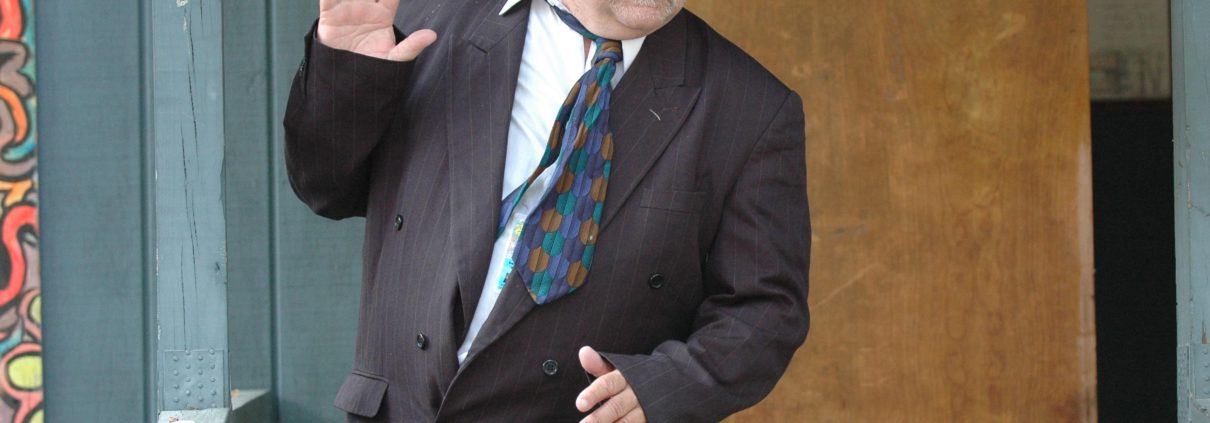

The col and I, Eddie’s Attic, 5-15-14. Photo by Rhiannon Bradley.

In a little room downstairs, I chatted a bit with Bruce and spoke at length with Jimmy. We were both somewhat star struck – Jimmy was thrilled that a Guitar World editor had so enjoyed his playing. I was gob smacked that someone like him cared what I thought, and convinced that I had just discovered a major talent. I was right, of course, and as silly as Jimmy’s excitement seemed then and still seems now, it was revealing about both his nature and the group’s circumstances.

“We were making $92 a week and sleeping in one room,” Hampton told me recently. “After two years we got two rooms and we were so ecstatic we had a celebration. There were five of us in a Chevrolet van with 400,000 miles on it. How we did it, I’ll never know, but I never had more fun or made greater music than I did during that run.”

No wonder Jimmy was so happy that I had taken note of this brilliant musical circus; they were playing for love and for each other and I was an outsider acknowledging their instincts were right, that they were onto something. There is no greater satisfaction for an artist than some affirmation that their struggling is not for naught, something they had received precious little of outside their Atlanta base.

This group of five had been playing together for about two years. Bassist Oteil Burbridge and drummer Jeff Sipe (then called Apt. Q258) had been with Bruce for about three more years. Hampton originally hired Oteil as a drummer. “We played about three gigs and then he picked up the bass one day and I said, ‘That’s what you’ll be playing from now on,” Hampton says with a laugh. “He was a good drummer, but he was like the greatest bassist I had ever heard.”

All the musicians came to Hampton as virtuosos. He opened up their boundaries. Hell, he obliterated the very concept of boundaries.

“Old timers would tell me that Oteil was playing too much, but the song was always there,” says Hampton. “He never lost that. And he was 21 and full of this amazing energy, so why not let him be free? Then I told him, whatever he wanted to do, do the opposite.”

But isn’t that a contradictory concept – be free and do the opposite of what you want to do? “Yes!” says Hampton. “That’s it.”

f that contradiction makes perfect sense to you, then you are well on your way to understanding Hampton’s Zambi musical approach, which Burbridge sums up in a few words: “Bruce was our professor of out.”

The Colonel’s educational role was obvious, but to this day he cringes at being called a mentor, even after 20 more years discovering great young players.

“I learn as much from them as they do from me,” he says. “What made me unusual was that everyone my age had either quit or made it. No one was playing clubs and putting together new bands on the cheap like that.”

Hampton had been making music in Atlanta since the late 60s. His Hampton Grease Band drew the attention of Duane Allman, who became a friend and supporter and got the group signed to Capricorn, who sold the contract to Columbia. Hampton says that their 1971 album Music to Eat is the label’s second worst selling album ever. Hampton spent the next 20 years working on his own and with the Late Bronze Age until he started putting together the ARU.

With Oteil at Wanee, 2014.

Hampton says that what he offered his young protégés was guidance. “They were already great when they joined the band, but what I did was try to break their boundaries,” he says. “I’d say, ‘Don’t be a fusion drummer or a blues bass player. Discover who you are.’ It was thrilling to discover all this together, and we went places that no one had ever been before – and very few people saw it.”

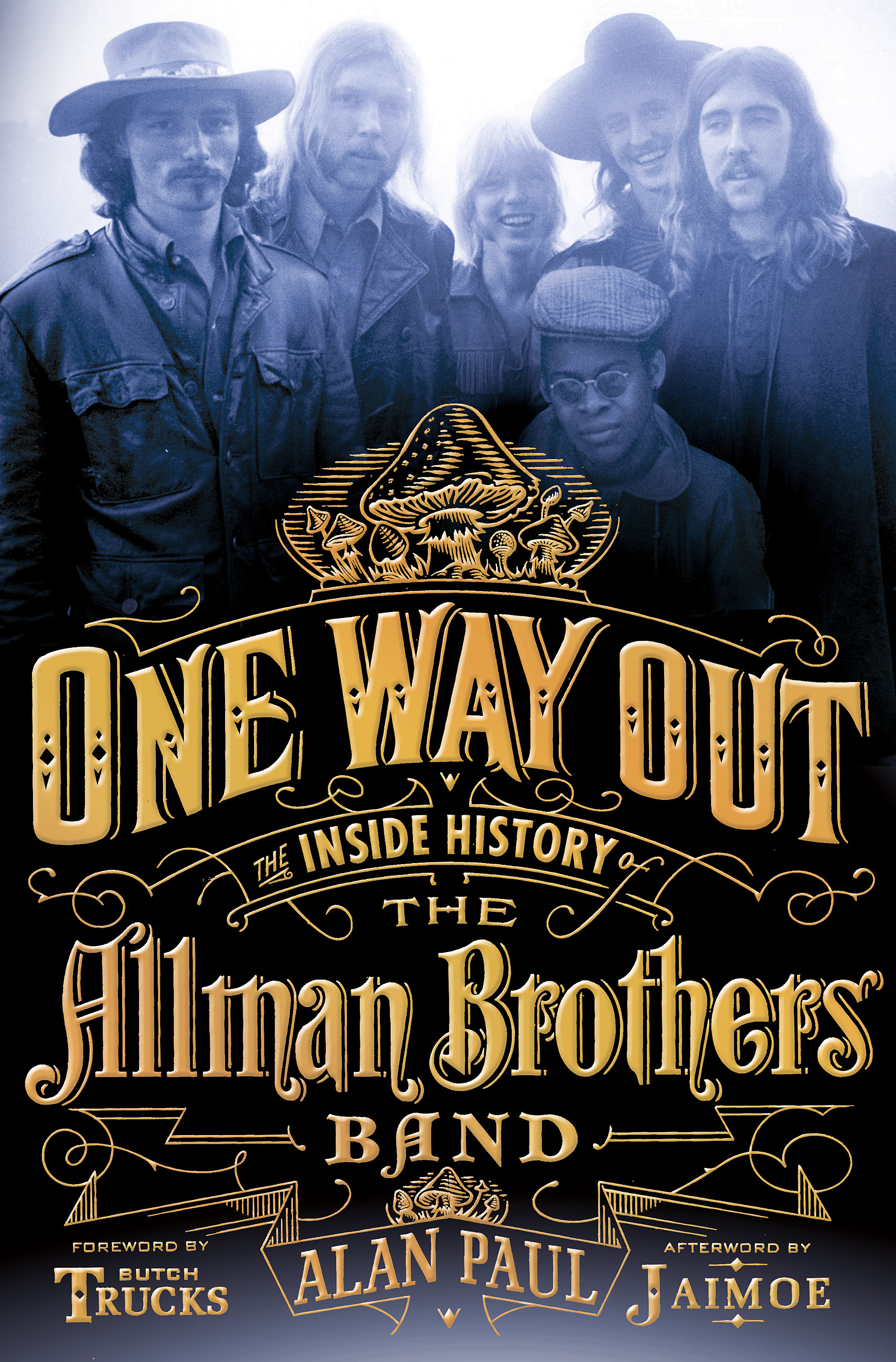

While their own shows may have rarely grown beyond large clubs, the ARU played on the early HORDE tours and became prime influences on the many bands and musicians, notably Phish, Widespread Panic and Derek Trucks, who was an honorary member by the time he could have been Bar MItzvahed. The ARU were the jam band Velvet Underground; a group whose influence vastly overwhelmed their commercial success. Most of the members went on to make their marks: Oteil as bassist of the Allman Brothers Band since 1998; Herring with the Allmans, Phil Lesh and the Dead and now Panic; Sipe with a range of bands. Mundy quit the group suddenly in 1993, giving up music. He plays again, though not publicly. Hampton has consistently put together great new bands, including the Fiji Mariners and the Codetalkers. Nothing in his approach to music has really changed.

“You either leave essence or you don’t,” he says. “ You either capture the moment or you don’t and you know at every show if you missed it or hit it, but you don’t know when it’s coming or where it comes from. That elusiveness is what keeps all artists going. But in the ARU, I think we only had one or two bad gigs in four years. Every night it was on and we would push each other to the outer limits. We sometimes played six or eight-hour gigs for 99 cents admission. In other words, we were a mental illness group.”

Anyone who heard this brand of illness either fell in love or scratched his or her head and walked away. But even as the band was earning converts, they were cracking under the strain of the road. Mundy’s departure cost them more than a unique musical voice. “He was the glue,” says Hampton, who quit touring himself within a year. The band continued for a few years with a couple of different singers, before everyone started drifting off to other gigs. They have reunited for brief tours and one-off gigs over the years, most recently at last year’s Christmas Jam in Asheville, North Carolina.

At that first show, I eventually said good bye to Jimmy, who had to load his own gear onto a trailer and push on, and went back upstairs to hear the Dregs. The playing was spectacular, but I couldn’t quite focus on the music. It was exemplary but it existed in the known universe. That no longer seemed like quite enough.

Good story, Alan! I got to see these guys a lot around Atlanta in the early 90s. That live record from the Georgia Theater still blows my mind to this day. Thanks for spreading the good word.

Right on.

I saw the band in the early 90’s and followed the ARU around in the south from town to town. I applaud this article. You are dead on. They were one of my biggest musical influences and Jimmy Herring still continues to impress and amaze. Check out his solo albums. Thanks!

Thanks Chris. I know Jimmy’s solo records… always love to hear him play.

Actually Matt Mundy joined Bela Fleck briefly before dropping off the scene completely. He helped his brother Mark out on Both Sides only album about that time, too, while of course appearing on WP’s eponymous sophomore release. Not until Chris Thile came along have I heard anything like him.

Thanks Jody. I actually did not know that he played with Bela after ARU.

I’m so glad Oteil was enlightened to his musical aspirations, as opposed to his acting ones.

Went to Clark u in Worcester, MA from 1991 to 1995. Saw ARU many times including opening for Phish in Albany. But the best we’re the relatively empty club shows. We stood in the front row in front of Jimmy and cheered after every mind blowing solo. He was so modest and thanked us with smiles and nods every time. One of my all time favorite live acts…great article.

Great article. I saw the ARU many times back then including in the front row of the Birchmere in D.C. which was basically some table chairs placed directly in front of the platform. It was amazing to sit 5 feet from these monsters and be shredded by Jimmy’s Fender Twin. I had the opportunity to speak with Jimmy a couple of times and he was always very gracious, humble and engaging. I’ll never forget the time that they played the HORDE and I somehow ended up backstage where I ran into him. During our conversation a bee came up and stung me in the eye. We cut the conversation short as I stumbled off to find the medical van. That still cracks me up all these years later. ha.

We (Philadelphia’s Rugby Road band) had the pleasure of meeting the colonel, jimmy, oteil, etc backstage at a show they were performing at the old Ardmore 23 East (now The Ardmore Music Hall ) back in 1994 or so. This article captures the jaw-dropping-holy-crap-I-can’t-believe-I-am-witnessing-this-and-why-are-we-the-only-ones-here?’ness of the ARU. An incredible band of incredible talent and incredible humbleness. We named our first record “Times Already Happened” after, in a conversation with the Colonel, I asked him what time they would go on and he responded “time’s already happened, I’m just filling in the spaces”. (minds blown)…We wrote a song called “Kind of Small” from that album as a tribute to the ARU (although in their vein of jazz-funk-fusion-slush, just a tip of the hat to their style, by no means could we pull their sound off – and featured the Colonel’s incredibly profound line in the lyrics – we also cover “Payday” live. We were also lucky enough to spend some time with the 2nd incarnation of ARU (Post-colonel) when their van broke down during their Philly stop on tour with Bruce Hornsby and we put them up at our house for the night. Jimmy drove off with a brand new Rugby Road baseball cap on and with 2 of our CDs in hand, I wish i had a cellphone camera back then because it was one serious proud moment to see a gentleman of his caliber sporting our merch. We all knew that the ARU was way too good for “commercial” recognition, and we liked it that way. We also knew that these guys were waaaay too talented to keep at it and that some bigger outfit would snatch them up – the Allmans, Phil Lesh and Widespread were smart enough to realize the added dimension that Jimmy and Oteil would add to their legacies. This article is perfect, well done and so good to see that others shared in our obsession with the ARU. Well written, thanks for the memories.