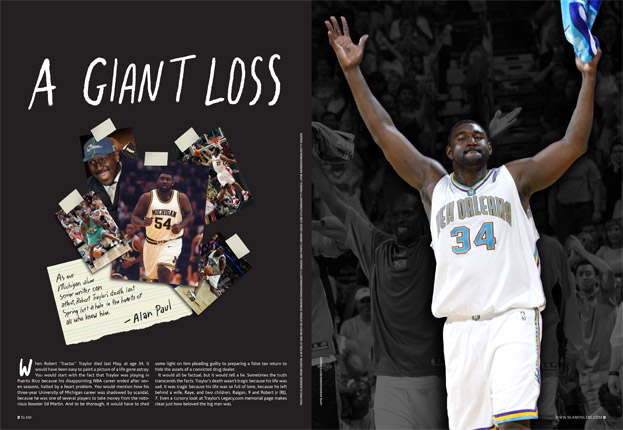

A Giant Loss: RIP Robert “Tractor” Traylor

A Giant Loss: My story looking back at the life of Robert “Tractor” Traylor is out in the current Slam, and is posted at @Slamonline.

I present it here as well. RIP Rob.

A Giant Loss

Robert “Tractor” Traylor’s death last spring left a hole in the hearts of all who knew him.

by Alan Paul | @AlPaul

When Robert “Tractor” Traylor died last May, at age 34, it would have been easy to paint a picture of a life gone astray. You would start with the fact that Traylor was playing in Puerto Rico because his disappointing NBA career ended after seven seasons, halted by a heart problem. You would mention how his three-year University of Michigan career was shadowed by scandal, because he was one of several players to take money from the notorious booster Ed Martin. And to be thorough, it would have to shed some light on him pleading guilty to preparing a false tax return to hide the assets of a convicted drug dealer.

When Robert “Tractor” Traylor died last May, at age 34, it would have been easy to paint a picture of a life gone astray. You would start with the fact that Traylor was playing in Puerto Rico because his disappointing NBA career ended after seven seasons, halted by a heart problem. You would mention how his three-year University of Michigan career was shadowed by scandal, because he was one of several players to take money from the notorious booster Ed Martin. And to be thorough, it would have to shed some light on him pleading guilty to preparing a false tax return to hide the assets of a convicted drug dealer.

It would all be factual, but it would tell a lie. Sometimes the truth transcends the facts. Traylor’s death wasn’t tragic because his life was sad. It was tragic because his life was so full of love, because he left behind a wife, Raye, and two children, Raigan, 9 and Robert Jr (RJ), 7. Even a cursory look at Traylor’s Legacy.com memorial page makes clear just how beloved the big man was.

Just click over and start scrolling through the messages, which share the same overwhelming emotions—true grief buoyed and tempered by real love. One relatively restrained post caught my eye:

I had the pleasure of… becoming a friend of Robert Traylor’s when he played at Michigan. As I paid my last respects… all I could think of was his great personality and competitive spirit as he wore #54. My sympathies and prayers go out to his family. —Bruce Madej, Associate AD, University of Michigan Athletic Dept.

Madej was the basketball sports information director when Traylor was at the University of Michigan. He set up a 1998 interview for me, conducted in the stands of Crisler Arena after a practice. Given the cloud that hovered over Traylor’s departure from UM, I wasn’t sure what his relationship with people there was like. But Madej and Coach Steve Fisher both returned calls about Traylor quickly, anxious to pay their respects to a young man each still called a friend.

“The people who are themselves and are genuine and who really care are the best people to be around, and he had that,” says Madej. “I loved the guy. He had an honest smile. He wasn’t contrived. What you saw is what you got, and what you got was a great guy.”

Fisher tells a similar story. Now the coach at San Diego State, Fisher recruited Traylor to Michigan and coached him there for two years.

“Robert was one of the kindest, most giving, caring people that I have come across—and not just in the world of basketball,” says Fisher. “He was simply a unique young man whom I loved deeply. I think he was always like that and everyone who met him understood.

“You could just see it in the way he treated other people—his peers, his classmates, his teammates, his neighbors and, most of all, the way he treated his family. The obvious love he had for everyone, starting with this grandmother, was exactly the kind of all-encompassing love we all want to have.”

Traylor’s family life was not simple. His mother abused drugs when he was a kid, so his grandmother took him in. Together the two of them collaboratively raised his younger brother.

Everyone looms larger after they pass away. Eulogies and obituaries inflate, mythologize and paper over flaws. But the more people you talk to about Traylor, the more obvious it becomes that this is different. Everyone repeats the same themes: He was a gentle giant; he was fun; he made everyone feel better; he really cared.

“Robert’s passing and his funeral were so emotional because he meant a lot to a lot of people,” said the Rev. Kenneth J. Flowers, who presided over the service and was Traylor’s cousin as well as his pastor. “If you met him once, you fell in love with him, because he was the kind of person who would give you the shirt off his back. He helped so many people that he almost died broke. He would spend $15,000 for a block party because everyone was like his extended family, especially in Detroit.”

Traylor was a Detroit man, through and through. As a 6-6, 250-pound freshman at Murray-Wright High School, he had to get his size 18 shoes from Pistons legend Bill Laimbeer, his coach once told the Detroit Free Press. As a junior, he led M-W High to city and state titles. As a senior, he was named Michigan’s Mr. Basketball and was the subject of an intense recruiting battle that boiled down to Michigan, Michigan State and Detroit-Mercy.

Wolverines fans reacted to his commitment like they had won the lottery, but Traylor had a long way to go. As a frosh, he was a manchild who simply tried to impose his will in the post. Over time, he developed into a deft, athletic big man, capable of passing out of the many double teams he faced.

“When you’re as physically dominating as he was, you are going to be double teamed and you have to be able to pass out of the post, and he really worked on that,” says Fisher. “He had to develop the skills, but his personality was reflected on the court. He gave of himself to others, did not care about stats. He was fiercely competitive, extremely intelligent and surprisingly quick—he had the footwork of a 160-pound guard.”

When Traylor entered the NBA Draft after his junior season, the only question seemed to be whether or not he would lose enough weight to silence the doubters. He seemed well on his way to stardom when he slimmed down while working out for NBA teams. I saw his changing physique first hand.

I was in the Detroit airport with my wife and infant son when our flight was canceled, leading to a panicked sprint to another gate, where about one third of us were going to be rebooked on to another plane. It was a survival-of-the-fittest moment and I wasn’t going to let my family perish. Turning into a new concourse at full speed, I almost ran into Traylor’s giant chest, pulling up just short of being pancaked. Slimmed-down, Tractor was still massive.

I laughed and reintroduced myself, his huge hand engulfing my forearm as we shook. “I’m sorry, but I have to go,” I said, taking off, before pausing 10 yards away to yell back, “Hey, Rob. You look great! Keep going!”

A smile split his face, and he chuckled. “Will do, man.”

The next week I was strolling the aisles of Toys R Us when I saw a Tractor Traylor bobblehead doll, which I bought and placed on my baby’s dresser.

Traylor was selected sixth in the ’98 Draft by the Mavs, then traded to the Bucks for the rights to a skinny German teenager. Many chuckled at the Mavs’ continuing foolishness. But of course, the lopsided trade ran the other way, and Traylor’s fate may have been sealed before any of us could have known. Dirk Nowitzki’s career soared while Traylor’s stalled, and the stigma became an ever-bigger burden for the mammoth man to bear.

“Everyone always talked about what a bad trade it was for Milwaukee as soon as they mentioned Robert’s name,” says Paul Silas, who coached Traylor twice, with the Hornets and the Cavs. “He was an offensive force in college, but he had trouble getting his shot off against bigger guys in the NBA. When the bad media attention came to him and people started smashing him, it really did a number on him.

“When I got him (in Traylor’s fourth season), he had lost his confidence and wouldn’t shoot, and I told him that he had to take any open shot. He got better, but what he really had to do was come to grips with who he was; he was a great rebounder capable of being a defensive force. I don’t think many coaches had expressed confidence in him, and when I did, he did a very good job.”

Traylor became fiercely loyal to the coach whose faith had helped his self-confidence. A year after leaving New Orleans and taking over the Cavs, Silas brought Tractor along, and their bond deepened.

“I was having some issues with the players and he took it up for me,” Silas says of Traylor, who played in 438 NBA games and averaged 4.8 points and 3.7 rebounds per outing. “I have not had many players ever do that, but I had gone to bat for him in Charlotte and now he went to bat for me. It’s hard to say just how much I appreciated that.”

Fisher and Silas tell remarkably similar stories about their relationships with Traylor over the years. Unlike many former players, they say, he didn’t just call when he wanted a favor. He genuinely wanted to stay in touch. He asked about their families and they knew it was because he cared, not out of politeness or shallow manners. And they both say that he was not bitter about his fate. He didn’t curse the world for having ended up a global basketball nomad.

Traylor failed a physical after signing with the Nets in 2005 when doctors discovered an enlarged aortic valve. He had heart surgery in November, 2006, then sat out a year and half before restarting his career overseas, in Spain, Turkey, Italy and Mexico. He moved on to his final stop, Puerto Rico’s Bayamon Cowboys, before last season.

In Puerto Rico, he quickly became the Cowboys’ most popular player, to the surprise of absolutely no one who ever met him.

“He was a leader of the team,” manager Jose Carlos Perez told the Associated Press after Traylor’s death. “He was very, very friendly. He got along very well with everyone. The fans loved him, idolized him.”

“Look, anyone who plays in the NBA and then ends up elsewhere wants to get back,” says Silas. “But Robert was very satisfied in Puerto Rico, making some money for himself and his family playing the game that he loved. He admired what he was doing and he wasn’t bitter. He just missed his wife and kids.”

Perez told the AP that Traylor was speaking to his wife on the phone when the connection cut off. Concerned, she called the team, who checked on him and found him deceased. Back in Michigan, now trying to pick up the pieces, a quiet but eloquent Raye Traylor is happy to talk about the man with whom she shared her life for 12 years.

“It was very hard for Robert to be away from us for so long, but he loved Puerto Rico,” she says. “He had made good friends and made himself a part of the community there, like he did everywhere else he ever lived. The kids missed him tremendously, and when he was home, there was only one place that RJ wanted be—with his dad. They spent all day together every day.”

Anyone who has ever been a parent or a child—everyone, that is—can understand the Traylor family tragedy. Seven-year-old RJ is lucky to be the son of someone who was so well-loved and who had so much love to give, and, of course, terribly unlucky to lose him at such an early age.

My own son is almost 14 now, and the Tractor doll is still on his dresser. It used to be a sort of kitschy marker of his Ann Arbor roots, but now it’s something else: a reminder of the fragility of life, and a totem of someone I’m happy for my boy to have as an idol. And that’s the truth.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!