Checking in with the North Mississippi All Stars

I’ll be hanging out with the Dickinson brothers in a couple of weeks at Butch Trucks’ Roots Rock Revival. Great guys, great band, great spirit. This story originally ran in Relix.

I’ll be hanging out with the Dickinson brothers in a couple of weeks at Butch Trucks’ Roots Rock Revival. Great guys, great band, great spirit. This story originally ran in Relix.

The Dickinson brothers.

It’s soundcheck at New Jersey’s South Orange Performing Arts Center and the North Mississippi All Stars are working out a new instrumental written by drummer Cody Dickinson, who is playing the gospel-tinged tune on a Nord keyboard set up on the perimeter of his kit. His brother Luther plays along with the changes on his Gibson 335 while Lightnin’ Malcolm leans against his amp and adds a loping, behind-the-beat bass line.

When they get lost for a moment and drop out, Cody keeps running through the changes, now calling them out: “It’s F to A flat to C – hold the C- back to F, G flat, F, E flat, hold the C, B Flat…”

As the band settles into the song, moving from hesitant to grooving, Luther adds some biting slide fills and smiles, as is his wont. “That’s nice,” he says. “What do you call it?”

“Hmmm…Let’s give it a working title: ‘Seeing Time.’”

Cody picks up a drumstick in his left hand and enhances the beat on a tom tom, as his right foot stomps the bass drum and his right hand continues to play the piano. The sketch is starting to sound like a song.

About 20 fans take in this scene, silently, reverently listening and watching. They paid extra for a VIP experience that allows them to meet the band and watch soundcheck and to a person they will say it was money well spent. This is an increasingly popular gambit by bands looking to strengthen their bonds with fans and improve their road take, and the All Stars are perfect candidates, because they genuinely enjoy interacting with people. They say that the experience has also been beneficial for the band, changing the way they soundcheck.

About 20 fans take in this scene, silently, reverently listening and watching. They paid extra for a VIP experience that allows them to meet the band and watch soundcheck and to a person they will say it was money well spent. This is an increasingly popular gambit by bands looking to strengthen their bonds with fans and improve their road take, and the All Stars are perfect candidates, because they genuinely enjoy interacting with people. They say that the experience has also been beneficial for the band, changing the way they soundcheck.

“I get full songs out of them now,” says soundman and longtime crewmember Randy Stinson.

“It makes us be a little more civil towards each other – and be more creative,” Luther says. “We can rehearse in front of an audience and I think that’s a plus. I was concerned about it hindering the creative process, but it has actually led us to come up with new segues and work up new material like the instrumental.

“You can get to a place and not feel like turning on and smiling, but the fans’ enthusiasm is infectious. You stagger in and someone smiles wide and shakes your hand and says, ‘I’m so happy to be here. I drove five hours to see you!’”

“That revitalizes your energy,” adds Cody. “It reminds you why you’re here, why you do this.”

Of course, the band probably drove at least five hours to see the fans as well, but that’s different. It’s their job, the life they’ve chosen. The life the Dickinsons were born into and embraced.

Cody and Luther’s father Jim Dickinson, who passed away in 2009, was a pianist and producer, a garage blues legend, best known for playing piano on the Rolling Stones’ “Wild Horses” and Bob Dylan’s Time Out of Mind and producing the likes of Big Star and the Replacements. As kids, Luther and Jim backed their father in the Hardly Can Playboys, before forming DDT, a punk band with a heavy Black Flag influence. At 14, Luther played a solo on the Replacements’ “Shooting Dirty Pool” from the 1987, Jim-produced Pleased to Meet Me.

About a year before that, the senior Dickinson had moved his family from the countryside East of Memphis to his old stomping grounds South of the city in the North Mississippi hills, with the express goal of furthering his boys’ musical education. It worked. Luther and Cody became close friends with the extended families of local blues patriarchs R.L. Burnside, Junior Kimbrough and Otha Turner, all of whose droning music –distinctly different than the better-known Mississippi Delta blues – seeped into the Dickinson boys’ souls.

In 1996, the brothers formed the North Mississippi All Stars, a group that pulled together all of these influences and debuted nationally with 2000’s Shake Hands With Shorty. That album distilled the magical, high-energy manner the brothers reinvigorated the blues with a raucous blast of fun that proved you could be reverential without being calcified. The group incorporated hip-hop beats and speed guitar runs without ever losing their blues grit and feeling. In the ensuing 13 years, they’ve added more and more elements and played with a rotating cast of bassists and other musicians. World Boogie Is Coming brings them full circle; it’s easily their most raw recording since Shorty.

“Our friend Seasick Steve knows our whole history and he said to me, ‘You’re the one, boy, the link,’” Luther recalls. “He said, ‘You have to keep it primitive and hold up your end of the bargain by taking it to the kids and making the blues attractive again.’ I realized I had not been holding up my end of the deal. The masters took me in and taught me so much – how to tour, how to keep the dance floor packed – and I had gotten caught up in my own songwriting trip.

Luther playing a Humingbird that may have been Duane Allman’s – last year at Roots Rock Revival

“We’ve really learned how to put everything in their proper place. Doing solo records and projects has allowed me to streamline what the All Stars should be. If I have some folk songs, there’s no need to force them into the All Stars just because I wrote them.”

The first song they recorded for World Boogie was an updated version of the blues classic “Rollin’ and Tumblin’,” with Luther laying down the main riff on a two-string diddley bow.

“We were doing an in-store appearance in North Carolina and my friend handed me a homemade coffee can two-string diddley bow guitar and I just tuned it up started playing ‘Rollin’ and Tumblin’,’” Luther says with a laugh. “We liked the way it came out and recorded it at our home studio, which we call the Zebra Ranch Electric Church and Fellowship Hall.

“That was the start of this record, though we didn’t know it at the time. We released it as a single, and were thinking that that’s what we would do: release singles.”

The shift in focus began when Cody, who has a growing interest in photography, recorded a video for the song, and the process jump-started a desire to record a song cycle that would be a “complete cultural statement.” Cody eventually cut videos for four of the songs, which can be seen at www.nmallstars.com.

“I’m real big on progress,” Cody says. “I don’t want to be stuck or static. When I see something that’s dynamic, I get excited and that’s how we try to push forward.”

When the band hit the road again, they began screening Cody’s films behind them and they continued to expand their footage, bringing cameraman Shelby Baldock with them.

Recalls Luther, “He filmed some stuff for us and we said, ‘We’re leaving on tour tomorrow. You have to come with us.’ It adds so much.”

Baldock watches the band from the side of the stage and keeps the film running behind them well synced and ever creative, often including local footage shot that afternoon. The films present a mesmerizing backdrop.

“It really helps the audience’s attention span,” says Luther. “It doesn’t really influence me – I can’t see it. But I can feel how it influences the audience and the vibe. It keeps their eyes on us, on the stage.”

Adds Cody, “I got into photography and acting – I’ve been in GI Joe and some other films. I understood that we needed a visual element and I wanted to stay away from laser lights. I hate stage lights. They make me sweat and look bad, and the projections allow us to mostly play in the darkness and to give people the multi-sensory experience they are so used to having. I love that we’re projecting. We’re coming to the future, but in such an old school way that it’s really the past, which is just perfect for us.

“Not only does it add a new dimension but it tells a story – and it looks cool. For instance, in the song ‘All Night Long,’ the movie shows concrete steps and bushes and it looks cool, but it’s deeper than that – it’s Junior Kimbrough’s juke joint. Obviously, most people don’t know that, but I still think they feel it, that it adds to the vibe.”

The Dickinsons have been profoundly impacted by their interactions in recent years with a trio of musical titans: Robert Plant, whose Band of Joy they toured with in 2011, and who plays harmonica on World Boogie; Phil Lesh, who has had the brothers out to California to play with his Friends; and Butch Trucks, the Allman Brothers drummer with whom the Dickinsons worked at the Roots Rock Revival camp last summer.

“These guys are giants of rock and roll and they’ve become friends and role models,” says Luther. “Touring with Phil and Plant and getting the chance to see them up close has been incredibly inspiring and instructive. They work really, really hard with total dedication to the music.”

Cody jumps in: “It’s a serious business and they take it very seriously.”

Luther nods his head in agreement and continues. “We were on tour opening for Plant when he was just doing his first shows with the Band of Joy and he was putting them through the paces, really making them work and learn a wide repertoire, some of which they didn’t even play. I think he wanted them to have the same music under their fingertips.

“And what Phil does – flying all these musicians in, working all day learning songs and arrangements, then playing shows at night, then starting all over again with a new crew – requires an incredible amount of work, patience and dedication.”

Cody sits across from this brother on their bus, nodding in agreement. It’s after soundcheck and before show time and the brothers are feeling expansive as they relax.

“Phil Lesh is a master,” Cody says. “Hanging and playing with him was the gig of a lifetime, just a total pleasure. After I was done, I had a completely new perception of what we do. Now I walk on stage with no preconceptions of what things should sound like, or where we should go. It’s like performance art.”

Cody generally sings one song a night, and it’s generally a different song every night, an approach which working with Phil pushed him towards. “The point is I’m pushing myself and losing all preconceptions of what I can do,” he explains. “It’s more like performance art and less like regurgitating what l Iearned in jazz band.”

Cody pauses for a second before continuing: “The payback to dedicating your life to something as abstract as being a touring musician is getting to pay with a master like Phil or Robert – or to sit and play double drums with Butch Trucks,” Cody says. “These are guys with finely developed musical personalities and visions. We learn so much and have so much fun interacting with them.”

Adds Luther, “Playing with Phil and seeing his dedication to sharing his passion and very distinct musical approach reminded me a lot of my dad, who used to always say, ‘If you learn something, it’s your responsibility to pass it on.’ I think that’s exactly what Phil is doing.

Trucks, Lesh and Plant could not have found more willing protégés for their mentorships. The Dickinson brothers have spent their lifetime learning from and collaborating with their father as well as

Turner, Kimbrough, Burnside and other Mississippi elders. Now those mentors are all gone, and in some ways their deaths may have drawn the brothers closer, underlining the bonds they share.

Says Luther, “When Cody and I play together I often think that this is the closest thing left to playing with Dad, and I think about that when I’m trying to be musically sympathetic, which is the key to being a team player; it’s the key to everything. I always just try to get in the moment and make something happen, and it’s not about fancy work. It can’t be, because what I play keeps getting simpler and simpler.”

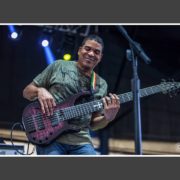

As we talk, bassist Lightnin’ Malcolm is on stage as the opening act, playing a duo show with single-named teenaged drummer Stud, the grandson of T Model Ford, who named the boy. Cody is pacing around and stretching, checking messages on his IPhone. Luther is reclining in the bunk of their bus, a Moleskin notebook in hand, poring through the pages, reading and making notes.

“This goes back to ’08 and has every setlist we’ve played,” he says. “I’m putting together a setlist and we never want to repeat songs we played last time in a place.”

The brothers are growing more quiet and contemplative as show time draws nearer, until Malcolm and Stud bound back on the bus. Seen up close, Stud’s youth is disarming. I ask him how old he is and he quickly answers, “Old enough.” In an hour, he’ll be jumping on and off stage with the All Stars, often parading around with a strapped on snare drum, sometimes taking over the kit so Cody can strap on an electrified washboard or a Telecaster.

The brothers are growing more quiet and contemplative as show time draws nearer, until Malcolm and Stud bound back on the bus. Seen up close, Stud’s youth is disarming. I ask him how old he is and he quickly answers, “Old enough.” In an hour, he’ll be jumping on and off stage with the All Stars, often parading around with a strapped on snare drum, sometimes taking over the kit so Cody can strap on an electrified washboard or a Telecaster.

Malcolm has been playing bass with the All Stars for about a year, though they’ve known him for much longer. Like most things in the band’s realm, his joining happened organically.

“We live really close together and he began coming over to my Airstream for songwriting and jamming sessions,” Luther says. When founding bassist Chris Chew took a friendly hiatus, the band played with Pierre Wells and Alvin Youngblood Hart, before Malcolm came on board.

“Hell, I don’t want to tell them this, but a lot of people could play what I do,” Malcolm says with a laugh. “I’m really a guitarist so when I play bass I just play half as many notes.”

“He brings a sensibility,” says Cody. “He knows the music and where we’re coming from, and we learn a lot from him, too.”

Luther and Cody exhibit a natural ease, like the music just flows through them. But it took a lot of effort to achieve that effortlessness, a lifetime of music being their lives, of incorporating their influences so deeply that they become one with them, of thinking, talking, eating, breathing music every day until it becomes inseparable from everything else.

“We know who we are and what we do,” Luther says with a smile, walking off the bus and heading for the stage door. It’s a Sunday night in suburban New Jersey and a theater full of people is waiting to hear some World Boogie.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!