Watkins Glen Summer Jam: the story behind the largest rock festival

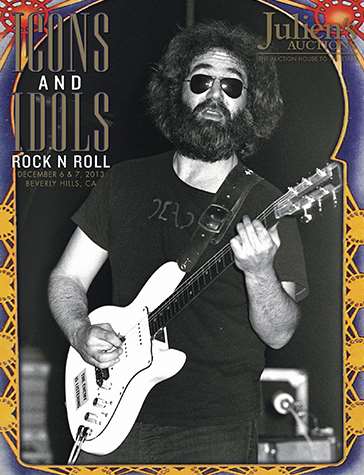

In honor of Jerry Garcia’s 75th birthday, I present this extensive, exclusive article on the Watkins Glen Summer Jam, at the time the largest concert ever. What an event. This story ran in a Grateful Dead one shot I wrote and edited for Parade along with the great GD historian Blair Jackson. We did great work and it was under-seen. I am trying to figure out how to get this out to more people.

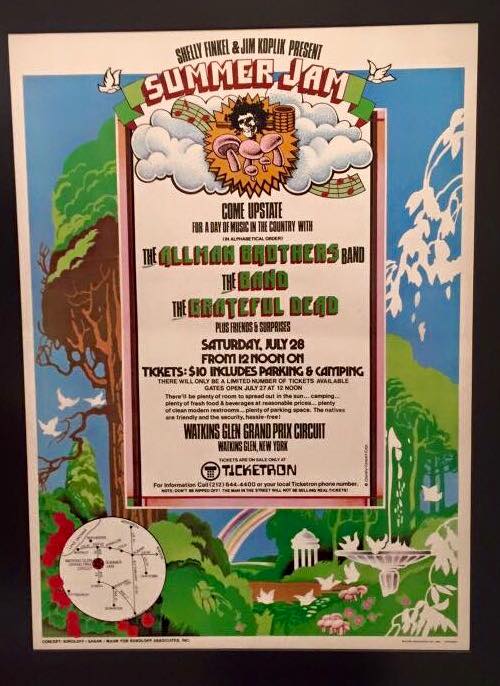

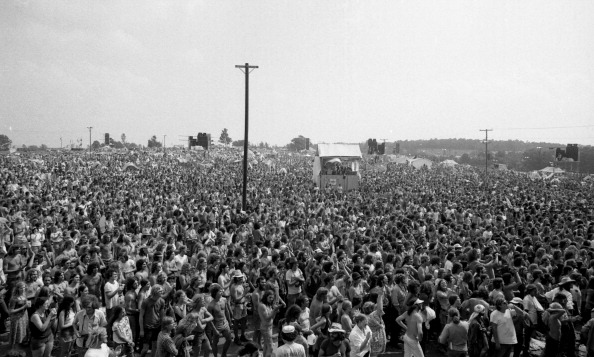

In 1973, the Grateful Dead, Allman Brothers Band and The Band teamed up for the Watkins Glen Summer Jam in New York’s Finger Lakes Region. It was the largest music festival ever, drawing about 650,000 people — nearly twice as many as Woodstock four years earlier. The festival was the culmination of a mutual admiration society between the Dead and the Allman Brothers that existed almost from the latter’s beginning.

In 1973, the Grateful Dead, Allman Brothers Band and The Band teamed up for the Watkins Glen Summer Jam in New York’s Finger Lakes Region. It was the largest music festival ever, drawing about 650,000 people — nearly twice as many as Woodstock four years earlier. The festival was the culmination of a mutual admiration society between the Dead and the Allman Brothers that existed almost from the latter’s beginning.

The Allmans were one of the first major groups to adopt the Dead’s two-drummer format in the late ’60s, and the Allman’s famous “Mountain Jam,” based on the melody of Donovan’s “There Is A Mountain,” first appeared as a brief musical quotation on the Dead’s trippy Anthem of the Sun in 1968, an album the Allmans knew well. The two bands first crossed paths in the summer of 1969 when they played for free in Atlanta’s Piedmont Park. The Dead, already well-established hippie heroes, arrived after the Allman Brothers, whose debut had not yet come out, had played, but they met and socialized. The ABB’s Duane Allman, Dickey Betts and Berry Oakley were particular fans of the Dead, a respect that was often returned by Jerry Garcia and the rest of the band.

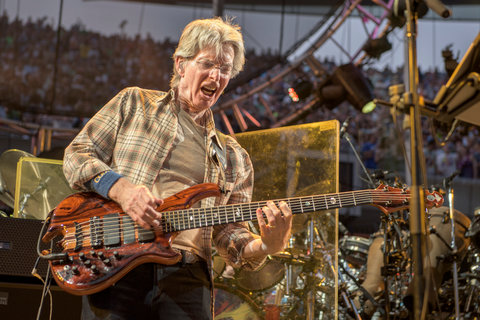

“We always loved playing with the Allman Brothers,” says Bob Weir. “It was clear from the first time we played together that we were kindred spirits.”

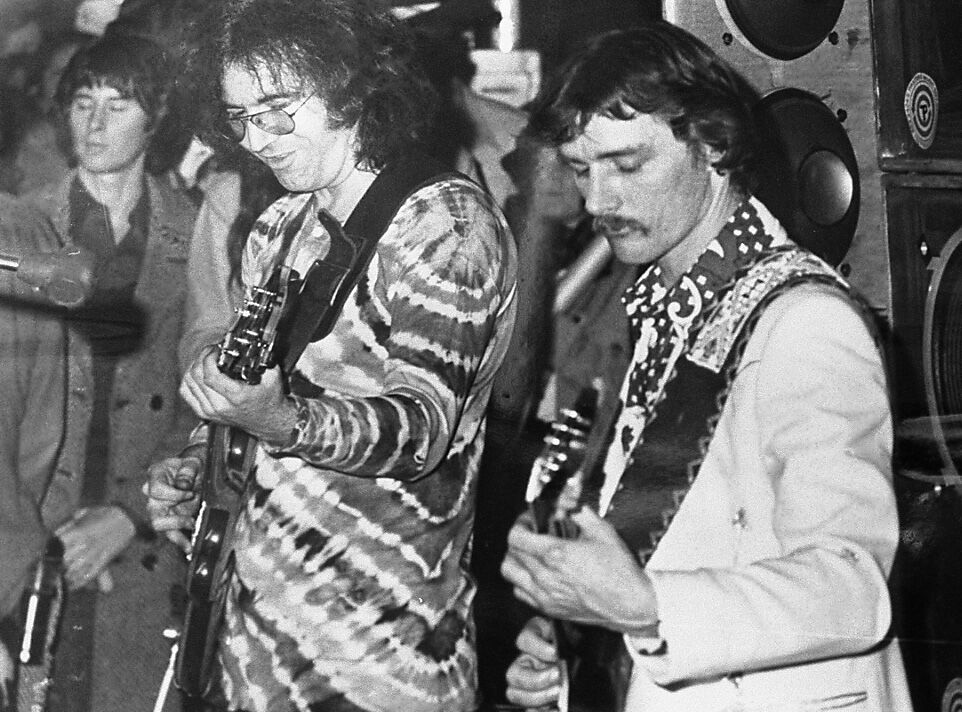

The two groups’ first bill together was three shows at New York’s Fillmore East, February 11 -14, 1970. The first night of the run featured an epic jam, with most of the Allman Brothers joining the Dead, along with guitarist Peter Green and other members of Fleetwood Mac, who were not on the bill. Over the next couple of years, there was just one more joint billing and a few sit-ins, even as the simpatico nature of both the musicians and their fans became more evident.

“The Dead’s philosophy was always very similar to ours,” Allmans Brothers guitarist Dickey Betts said in 1994. “We sound very different, because we’re from different roots. They’re from a folk music, jug band, and country thing. We’re from a urban blues/jazz bag. We don’t wait for it to happen; we make it happen. But we’ve always had a similar fan base and philosophy — keeping music honest and fun and trying to make it a transcendental experience for the audience.”

Duane and Jerry often expressed admiration for one another’s each other’s work, and a friendship was budding. Duane even popped into a Boston radio station on November 21, 1970, when Weir and Garcia were performing acoustically. He picked up a guitar and joined in. Six months later, during the Dead’s final week of shows at the Fillmore East, Duane turned up for the April 26, 1971 and added his distinctive sound to three tunes.

“We developed a close relationship with Duane that unfortunately never had the time to blossom because he was gone so soon,” says Weir.

Following Allman’s death in October 1971, the two bands finally planned a few joint shows together, which Dead crew member Steve Parish described as “trying to support our friends” during a difficult transition. The performances were scuttled when Oakley died the night before the first scheduled show, in Houston. By the time the bands finally played together again, on June 9 and 10, 1973, they had both grown so popular that they co-headlined Washington DC’s RFK Stadium, alternating opening and closing slots.

On July 28, they topped two nights at a stadium with the Watkins Glen Summer Jam. The one-day festival was planned by the Dead’s Sam Cutler and the Allman Brothers Band’s Bunky Odom. They agreed together to invite The Band to open the day’s music.

“We thought those three bands represented America,” says Odom. “They were the three best American bands and they related to each other, the music related, the fans related and they all knew each other. It was just a great fit.”

The concert was planned for the Grand Prix speedway in the remote hamlet of Watkins Glen, New York. The concert was produced by two young promoters Jim Koplik and Shelley Finkel, who paid the Dead and Allman Brothers $110,000 each. One hundred and fifty thousand tickets were sold for $10, but the crowd exploded to many times that number. The rest got in for free, though many of the masses certainly never got within sight of the stage. The small country roads leading to the concert site became parking lots – first figuratively, then literally, as many people abandoned their vehicles and walked miles to the concert.

“It was hard to get in and out of that place,” says Weir. “It got way, way bigger than we intended for it to get. We thought maybe if we’re lucky we’d get 100,000 people; 60-70,000 would be nice and handle-able.”

The bands were staying 18 miles away in a small motel in Horsesheads, New York. The day before the festival they were supposed to soundcheck but the roadways were completely blocked by people abandoning their vehicles in the standstill traffic and walking to the raceway grounds.

Jerry and Dickey, NYE 73. Photo – Sidney Smith

“When we first got there we were able to drive in and out of the site, but the road became like Armageddon overnight,” says Allman Brothers tour manager Willie Perkins. “It was like there had been a nuclear attack and people had just abandoned their cars.”

It was obvious that the band and crew would not be driving to the concert ground. Helicopters were summoned and as they drew close, the passengers asked the pilot to circle the site.

“We wanted to soak it in and it was absolutely stunning, exhilarating and exciting to see this incredible mass of human beings,” recalls Allman Brothers keyboardist Chuck Leavell. “It was an ocean of bodies. We were all just really buzzed by the whole scene and situation.”

“All the stuff like transportation just broke down,” says Parish. “Amenities were impossible to maintain, fences were broken down. It became a serious security situation for the crowd, but the stage was secure.”

With crowds pouring in and an estimated 200,000 people already on site, the July 27 soundchecks became public performances. The Band did about 45 minutes. The Allman Brothers pushed close to two hours, and the Dead did an almost-complete show. The one-day festival had organically doubled in length.

Recalling the soundcheck still registers amazement in the voice of Allman Brothers drummer Butch Trucks. “That afternoon rehearsal ended up being my most powerful memory because in daylight you could see 600,000 people stretched out in front of you and my God! What a sight!” he says. “Everyone should get up in front of 600,00 people some time in their life. It’s sort of intimidating but also very, very inspiring.”

At Cutler’s insistence, the promoters had hired Bill Graham, a key figure to both the Dead and Allman Brothers, to handle the staging and backstage area. Graham had taken his usual care in constructing a welcoming backstage area, which Perkins recalls as “idyllic.” Palm trees were brought in and most band members had their own trailers, traipsing in and out of one another’s spaces, with endlessly mutating jam and hangout sessions. Leavell, Kreutzmann, Garcia and Jaimoe seemed to particularly enjoy playing with one another. In his memoir, Deal, Kreutzmann writes that his best memories of the Summer Jam was playing with Jaimoe backstage.

While the bands were enjoying each other’s company, the crowd just kept swelling. Impossibly hot weather was interrupted by rain storms, but things remained mostly calm and friendly. In A Long Strange Trip: The Inside History of the Grateful Dead, Dennis McNally reported that the county sheriff said, “We have four or five times as many people here as we have at our races, and we are getting less than half the trouble. These kids are great.”

“The news reported there were 600,000 there and maybe 2 million people in the area and it was declared a disaster area,” recalls Weir. “As disaster areas go, it was a pretty nice one, but people who were interested in going home, for instance, well, they couldn’t. If they wanted to leave, it just wasn’t possible. People had to be peeled away by layer by layer.”

Each of the band’s performed long sets. The Dead opened and were followed by The Band, who had not played together in a year. Their performance was interrupted by a thunderstorm before the Allman Brothers closed out the day with a four-hour performance capped by an all-band jam. Legend and the band’s own deprecatory comments have it that as with Monterey Pop in 1967 and Woodstock in ‘69, the Dead’s performance was limp. While the show was never officially released, widely circulated recordings indicate it was stronger than the band itself recalled. Still, most Deadheads swear that the soundcheck performance was more powerful.

“We got the short stick on who would open and who would close,” says Weir. “As I recall, it was essentially determined by drawing cards out of a hat because it was impossible to rank the bands. It would have been nice to have the lights and we didn’t get them because we played in daylight. I do remember the jam at the end was pretty spectacularly wiggy.”

One can debate whether Weir meant to say the jam was great or terrible—but Allman Brothers drummer Butch Trucks is far more direct in his assessment: “The jam was just ridiculous, because by the time we all got together everyone was fucked up — and fucked up on different drugs. The Band was all drunk as skunks and sloppy loose, the Dead were full of acid and wired in that far-out way, and we were all full of coke and cranked up. You put it all together and it was just garbage. While we were playing, we thought it was the greatest thing the world had ever heard, but then we listened to the playbacks.”

Five months after the landmark concert, the Allman Brothers played the Cow Palace in San Francisco on New Year’s Eve, in a performance nationally broadcast on radio. The Dead were off that night, and Garcia and Bill Kreutzmann sat in for much of the second set and encore, with Kreutzmann taking over for Trucks, who was dosed with LSD and unable to continue playing. The friendships between the two titans of the jam rock world seemed to be growing, but they would never again share a bill.