The Definitive Voice of Rock History

Alan Paul

New York Times Bestselling Author

Journalist

Musician

Speaker

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

"Alan Paul is rock’s finest narrative storyteller.”

– Premier Guitar

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

“No journalist knows the ins and outs of the Allman Brothers Band better than Alan Paul.”

-Warren Haynes, Allman Brothers Band

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

“If you want to know the real deal, read Alan Paul.”

-Oteil Burbridge, Allman Brothers Band

Alan Paul is a New York Times bestselling author, acclaimed music journalist, and the definitive voice on the Allman Brothers Band. With deep reporting, unforgettable storytelling, and rare insider access, his books bring the soul of rock history to life.

FEATURED WORKS

Bestsellers That Tell the Untold Stories of Rock

ABOUT

Telling the Stories That Shaped Rock, Culture, and Generations

Alan Paul is a best-selling author, journalist and musician. His last three books have been instant New York Times best sellers. He is widely regarded as the foremost expert on the Allman Brothers band and is an experienced public speaker and interviewer.

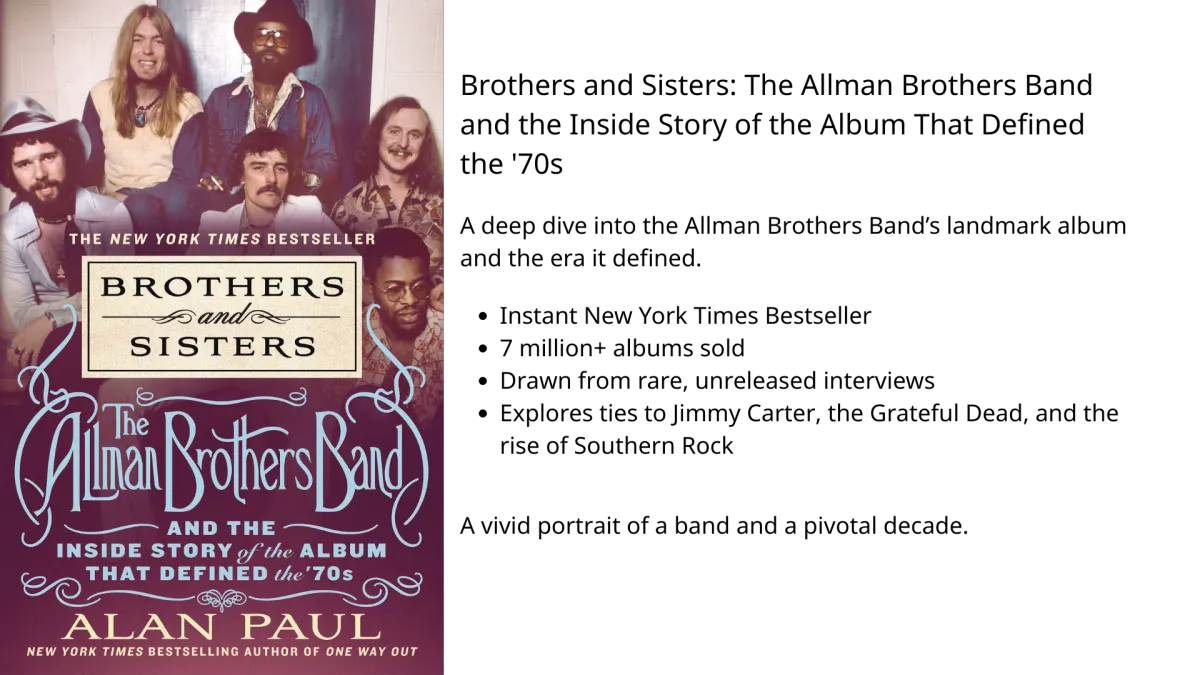

His most recent book, BROTHERS AND SISTERS: The Allman Brothers Band and the Inside Story of the Album That Defined the 70s, was his third straight instant New York Times bestseller. The book is a deep dive into the time before and after 1973’s Brothers and Sisters, which was not only the band’s best-selling album, at over seven million copies sold, but it was also a powerfully influential release, both musically and culturally, one whose influence continues to be profoundly felt.

Celebrating the album’s 50th anniversary, Brothers and Sisters the book delves into the making of the album, while also presenting a broader cultural history of the era, based on first-person interviews, historical documents and deep research and a trove of never-before-heard interviews conducted by the band’s “Tour Mystic,” Kirk West.

The five-year period between Duane Allman’s 1971 death and the Allman Brothers Band’s 1976 breakup was a remarkable run for the group that helped define the era, rock history and American culture and politics. They played a major role in electing President Jimmy Carter; were intimately linked with the Grateful Dead; and inspired the Marshall Tucker Band, Lynyrd Skynyrd and the entire Southern Rock genre. Gregg Allman’s marriage to the iconic star Cher also put the couple at the vanguard of a newly emerging celebrity media culture.

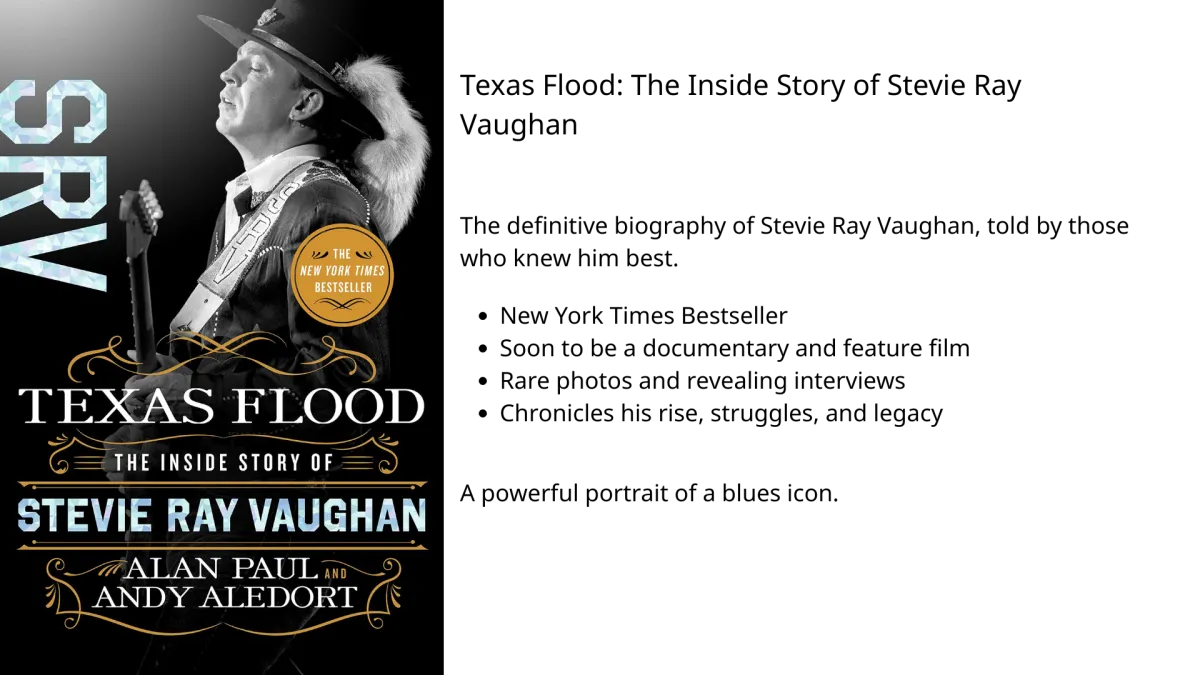

Paul’s previous book Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan has been optioned and is being developed for both documentary and feature films.

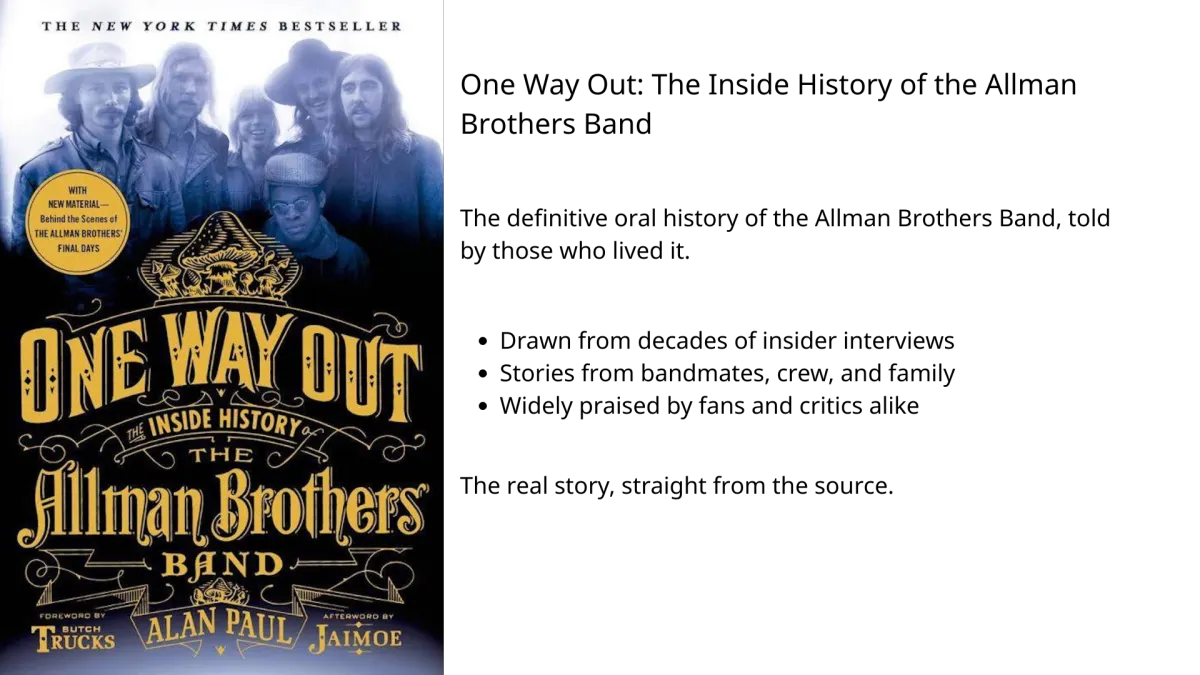

One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band is widely considered the definitive history of the ABB and marked the beginning of Paul’s run of best sellers.

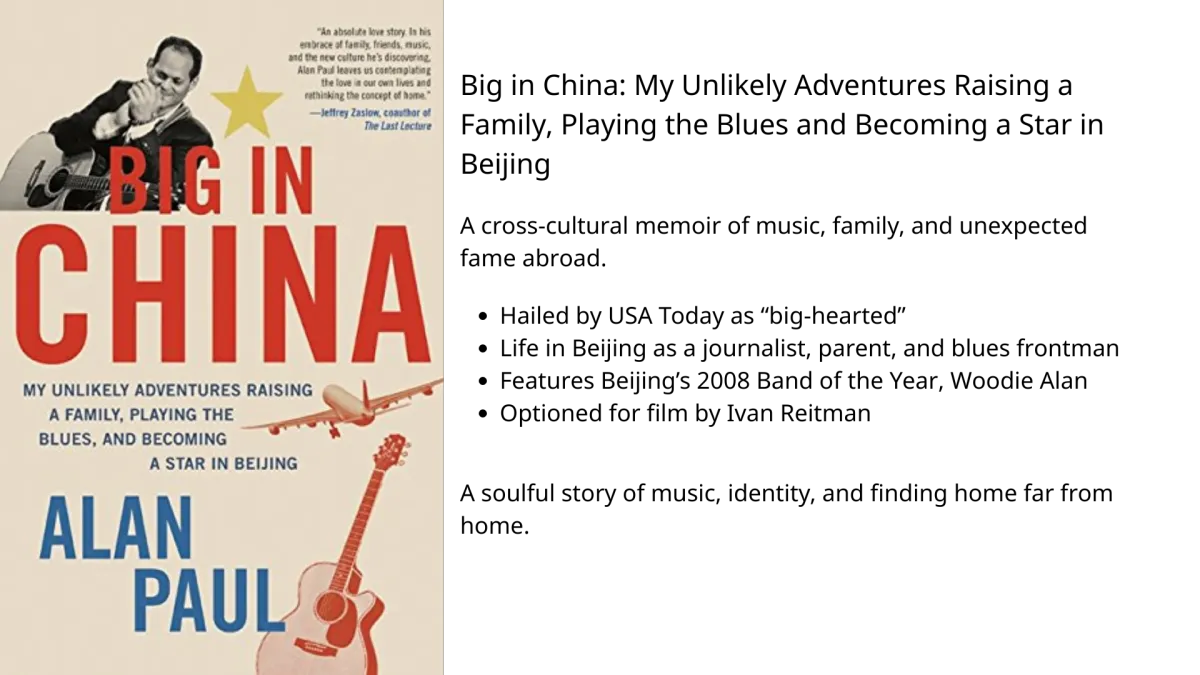

His first book, Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing was hailed by USA Today as a “big–hearted memoir with emotional depth.” It is about his experiences raising three American children in Beijing and Paul’s unlikely journey to becoming a Chinese music star, fronting the blues band Woodie Alan, Beijing’s 2008 Band of the Year.

It was optioned for film development by Ivan Reitman. That band’s debut CD Beijing Blues was an East/West fusion that earned praise from ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons and the Allman Brothers Band’s Warren Haynes.

Published in The Wall Street Journal, Guitar World, and Relix

Telling the Stories Behind the Songs

Beyond his best-selling books, Alan Paul’s writing has appeared in some of the most respected music and culture publications. His work combines deep reporting with personal insight, often giving readers a front-row seat to the emotional truths behind legendary artists and moments in music history.

From reflective tributes to revealing profiles, Alan’s voice has become essential reading for fans of rock, blues, and American culture.

Please Call Home: Alan Paul Remembers Gregg Allman

Published in Relix Magazine

A deeply personal and beautifully written remembrance of Gregg Allman, exploring his artistry, legacy, and humanity.

Alan Paul Remembers Butch Trucks: “The World Feels a Lot Quieter, a Lot Smaller, and a Lot More Boring”

Published in Relix Magazine

A moving tribute to drummer Butch Trucks, reflecting on his intensity, humor, and irreplaceable role in the Allman Brothers Band.

How the Allman Brothers Band Helped Make Jimmy Carter President

Published in The Wall Street Journal

An eye-opening look at how Southern Rock legends became political allies, this article traces the Allman Brothers Band’s critical role in Jimmy Carter’s presidential campaign and how music shaped a movement.

Behind the Scene: Alan Paul Revisits the Allman Brothers, NBA Journalism, and Being Big in China

Published in Relix Magazine

An in-depth conversation with Alan Paul about his multifaceted career — from covering the Allman Brothers Band to reporting on the NBA and becoming a music star in Beijing.

Alan Paul is the founder of Friends of the Brothers — the ultimate live experience honoring the music, spirit, and brotherhood of the Allman Brothers Band. More than a tribute act, this group is a living, breathing continuation of the ABB legacy, built on deep relationships, authentic sound, and decades of musical history.

Featuring members of the Gregg Allman Band, Dickey Betts Band, and Jaimoe’s Jasssz Band, the lineup is a direct extension of the ABB family. Regular appearances by Jaimoe, the last surviving original Allman Brother, make every show both a musical powerhouse and a sacred reunion for longtime fans.

These performances are filled with the raw improvisation, soulful grooves, and emotional fire that defined the original band. Each setlist is built with love and reverence, pulling from every era of ABB’s iconic catalog — from "Blue Sky" and "Melissa" to "Whipping Post" and beyond.

Rolling Stone’s David Browne wrote:

“Though they honor the music, Friends of the Brothers never feel like a tribute band. They play the songs as if they’d written them.”

For ABB fans, these shows are more than concerts — they’re gatherings. Moments to remember, reconnect, and keep the flame alive.

Over 1,900 Transformative Narratives

Revamping Lives. One Narrative at a Time.

“Happily, Paul is far more interested in music than gossip, and has a knack for writing about the way it sounds and how it makes people feel. He’s at his best tracking influences, dispelling myths and half-truths, and teasing out similarities and differences between players.”

- Eric Pooley, The Observer

“Few writers understand or appreciate the Allman Brothers as much as Paul. His book, which coincides with the 50th anniversary of its namesake album, colorfully narrates an oft-overlooked chapter in the band’s history with nuance, clarity and perspicacity. In addition to his own extensive reporting, Paul had access to hundreds of hours of interviews conducted in the mid-1980s by Kirk West, a longtime Allman Brothers insider, for a book West never got around to writing. That material gives Paul’s work a real richness and depth. Brothers and Sisters is a very good read for anyone interested in the Allman Brothers, the sounds of the ’70s or simply great music. It rocks.”

- Los Angeles Times

“Paul’s previous book, One Way Out, is a fascinating oral history written with the band’s participation, capturing various highs and lows from the 1960s right up to the years just before their final show in 2014. Paul’s latest Allman Brothers book, though, is even more rewarding. It’s a traditional narrative featuring Paul’s clean, smart, conversational prose, which he uses to make a strong case for Brothers and Sisters indeed being the definitive album of the 1970s. The book also explores how the Allman Brothers played an important role in getting their Georgia governor, Jimmy Carter, elected president and delves into the band’s relationship with the Grateful Dead, leading to one of the largest rock festivals of all time, Summer Jam at Watkins Glen. The “Brothers and Sisters” book utilizes previously unheard interviews with key figures, including Betts and Allman, conducted by Allman Brothers archivist, photographer, and “tour mystic” Kirk West in the mid-1980s, during the band’s second hiatus.” -Wade Tatangelo, Sarasota Herald-Tribune.

- Wade Tatangelo, Sarasota Herald-Tribune

BEYOND THE BOOKS

A Familiar Voice in Print, On Air, and at Home

Alan Paul is more than an author. He is a seasoned storyteller, a trusted cultural historian, and a respected voice in the world of music journalism. As a longtime contributor to The Wall Street Journal, Guitar World, and other leading publications, he has spent over two decades chronicling the lives and legacies of some of music’s most influential figures.

His work goes far beyond surface-level reporting. With a unique ability to draw out personal truths, Alan has conducted hundreds of in-depth interviews with legendary artists, producers, and insiders. These conversations reveal not just what happened, but why it mattered. His passion for music, paired with a strong instinct for narrative, allows him to illuminate the human stories behind iconic sounds.

Alan is also a regular guest on national radio shows and music podcasts, and a sought-after speaker for author panels, conferences, and university events. Whether unpacking the rise of Southern Rock, exploring the cultural reverberations of the Allman Brothers Band, or tracing the roots of the American blues tradition, he brings clarity, depth, and soul to every conversation.

What sets Alan apart is more than knowledge. He approaches every stage, studio, and page as both a journalist and a lifelong fan. He honors the music and the people behind it. From keynote addresses to intimate roundtables, he connects through storytelling and transforms decades of research and lived experience into something vivid, accessible, and deeply human.

FEATURED ON

© 2025 Personal Branding Launchpad. All rights reserved.