From the archives: Making of Layla

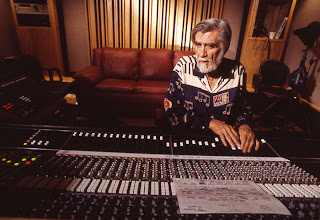

Tom Dowd was one of the greatest producers of popular, 20th century American music –working with everyone from Charles Mingus, the Drifters , Ray Charles and Aretha Franklin to the Allman Brothers, Lynyrd Skynyrd and Cream. He was also a great guy and a brilliant raconteur, who loved to entertain with tales from his long and storied career.

I interviewed him many times for many stories. I wrote the following for Guitar World over a decade ago, for the Producers column. One of my favorite memories of my career was sneaking into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony at the Waldorf Astoria the year the Allman Brothers were admitted — a major coup that required grapefruit cajones, by the way, but that’s another story. After making the break from the press room into the hall, I drifted around and ended up at one of the Allmans tables, with Kirk West, my buddy and an ABB manager. He was tickled to see me, couldn’t believe i had breached the security, and gave me an invisible ink hand stamp under the table which made me legit.

The night was coming to a close and I found myself next to Tom Dowd. He filled up our wine glasses with a bottle of red on the table. As Neil Young and others took the stage for a jam, Tom regaled me with the story of how Otis Redding wrote “sitting on the Dock of the Bay” as his first song after Steve cropper had given him an open tuned guitar. He told me all about the song and the recording process of it — he produced that, too. R.I.P. Tom, you were a gentleman.

**

Tom Dowd began his career as a house engineer and producer for Atlantic Records, recording classic sides by Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, Otis Redding, John Coltrane and others. But for all his contributions to the worlds of jazz and r&b, Dowd was to make his biggest mark in rock, most notably working with Cream and, later, Eric Clapton, and the Allman Brothers Band, a relationship which began with the group’s second album, Idlewild South (Capricorn, 1970), and continues to this day. So he was uniquely qualified to bring together Clapton and Duane Allman, a casual introduction which led to the creation of one of rock’s undisputed masterpieces, Layla and And Other Assorted Love Songs (Polydor, 1970).

“I was working with the Allman Brothers on Idlewild South when I got a call from Robert Stigwood saying that Eric would like to record and asking if I could fit him in my schedule,” recalls Dowd. “Of course I said I’d be delighted. It became a lengthy conversation and as I usually didn’t take calls while in session the Allmans had all wandered in wondering what the hell was going on. I put the phone down and said to Duane, ‘You have to excuse me, that was Eric Clapton’s manager. They want to come here and record,’ and he said, ‘You mean this guy?’ and plays me an Eric solo note for note. I said, ‘That’s the one’ and he goes, ‘I got to meet that guy. You got to let me know when he’s gonna be here. I’d love to come by and just watch him. Do you think that would be possible?’ And I told him I was sure it would be fine, and he should call me and we’d work it out.

“Sure enough, two or three weeks later, Derek and the Dominos are in the second day of recording and Duane calls and goes, ‘Is he there? We’re gonna be in Miami tomorrow for a concert. Can I come by and meet him?’” I said, ‘I’m sure you can. Hold on.’ I grabbed Eric and said, ‘I have Duane Allman on the phone. His band is playing in the area tomorrow and he’d like to come by and meet you.’ And he goes, ‘You mean this guy?’ and he plays me Duane’s solo off of Wilson Pickett’s ‘Hey Jude’ note for note. I said, ‘That’s the guy.’ And he goes, ‘I’ve got to see him perform. We’re going to that concert.’”

“Now I knew the two of them personally and they were both low-key, beautiful human beings and wonderful musicians, so I thought, ‘This is gonna be fun.’ Sure enough, Saturday afternoon, we record for a few hours, then head out to the limos Eric had waiting and go down to the Convention Center, where the Allman Brothers are playing. They snuck us in behind the photographer’s barricade, sitting on the floor with our backs to the audience, right in front of the stage. Duane’s in the middle of a solo, when he opens his eyes, looks down, sees Eric and stops playing cold, in shock. Dickey starts playing to cover until Duane regains his equilibrium, and then he sees Eric and he freezes too. That’s how big Eric was to them.

“After the show they met and hung out and all of a sudden I had half the Allman Brothers and all of Derek and the Dominos crammed into a limousine going back to Criteria, where they jammed until two or three the next afternoon. I kept the tape running the whole time. [Some of these jams appeared on The Layla Sessions (Polydor, 1990)] There’s Duane playing Eric’s guitar and Gregg playing Bobby Whitlock’s organ and they were all in piggy heaven. When it was over, they were all such good friends and Eric said to Duane, ‘When are you coming back? We should record some.’”

The Brothers had some tour obligations to meet but, Dowd recalls, Duane vowed to return as soon as possible. “Sure enough, two or three days later he called up and said, ‘I’ll be back tomorrow.’ By the time he returned, the Dominos had recorded several songs and had arrangements set for others, but right away he started fitting in parts and the more he did that, the more their reaction was, ‘If he’s gonna do that, I’m gonna do this.’ Songs started to radically change because Duane had unleashed this dynamic entity that was just ridiculous. They were feeding off each other like crazy and running on pure emotion.”

Clapton and Allman were set up in the studio facing each other, looking one another in the eyes and playing live through small Fender amps–a Princeton and a Deluxe. “These guys weren’t wearing earphones,” Dowd recalls. “They were just playing softly through those little Fenders. If they talked while they were recording, you would have heard it over the amplifier. It’s funny, too because when I did Cream, Eric was playing through double stacks of Marshalls and it literally hurt to be in the room with those guys. When Eric showed up for Layla, he had a Champ under one arm and a Princeton under the other and that was it. He and Duane used those amps, switching back and forth.”

The two also often swapped guitars, with Clapton primarily playing a Strat, Allman a Les Paul. “They did whatever seemed best at the moment for a given part,” Dowd recalls. “It was never gonna happen again. It just happened and if you didn’t catch it, you blew it. The spontaneity of that whole session was absolutely frightening. A lot of it flew and then when they heard it, they’d say, ‘Oh man, here’s a part I gotta put in there.’ But it was not because it was misplaced the first time, but because they would have another flight of inspiration when they could step back and hear it. They had all this positive feedback to add. There was no jealousy or ego-type thing at all among them.”

Also, Dowd adds, contrary to ever-growing legend, there was no excessive drug use during the album’s actual recording: “We started sessions every day at 2:00 and everyone arrived clear eyed and ready to work. As I dismissed people, they may have floated away, but it did not interfere with the album. Even in his wildest moments, Eric arrived at the studio on time with his instrument in tune, ready to play — and he would give absolute hell to anyone who didn’t. Eric and Duane shared that. They didn’t know each other from Adam before the sessions began, but they were both taskmasters. They didn’t give a damn what anyone did on their own time, but when they were in the studio, it was their time, and you better be ready to go.”

After approximately two weeks of recording, the band went out on the road and Duane returned to the Brothers, leaving Dowd to mix the album on his own. “I sent them cassettes and then Eric called and said they wanted to come back to alter a part on one or two songs and remix one song. When they returned–with Duane–among the things they had in mind was adding a piano part to ‘Layla’ and I thought, ‘Oh my god, where does it go? The song is tight as a drum’ I played them the cut, mixed, and they said, ‘Okay it’s going to go here and we’re going to do this and that.’

“I thought, ‘You’re all absolutely stark-raving mad. How are we going to get everyone to match the brilliance of what they did the first time and make it fit?’ But I had no choice, so we gave it a go.”

Drummer Jim Gordon, who played the coda’s piano part is credited with writing it as well, a fact which has been disputed over the years. Dowd says that no one ever explicitly told him who wrote the music, but Gordon played it beautifully, in one take.

“When I set up, I expected Bobby Whitlock to play the piano, but [drummer] Jim Gordon played it. I can’t say whether or not he wrote it, but he had it mastered; that part was in the end of his fingers. Duane’s guitar part on that coda is just absolutely intense and, of course, I was absolutely wrong about not being able to make the new part fit. We spliced it right in and it made the song. I knew immediately that we had something really, really special –as anyone would have.

“The whole session was just so damn impromptu and fly-by-the-seat-of-your- pants brilliant. It was just a wonderful experience to witness such meshing of musical minds, such telepathic sympathies. When we walked out, I told the band, ‘This is the best damn album I have done since The Genius of Ray Charles.’ And then the damn album didn’t sell for a year. We all knew how great it was –including everyone at Atlantic –but we couldn’t get arrested with it. That was very hard to understand, and very disappointing. Then a year later ‘Layla’ was like the national anthem. And that seemed appropriate.”

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!