The Trail He Blazed: RIP Earl Lloyd

Original Old School: The Trail He Blazed

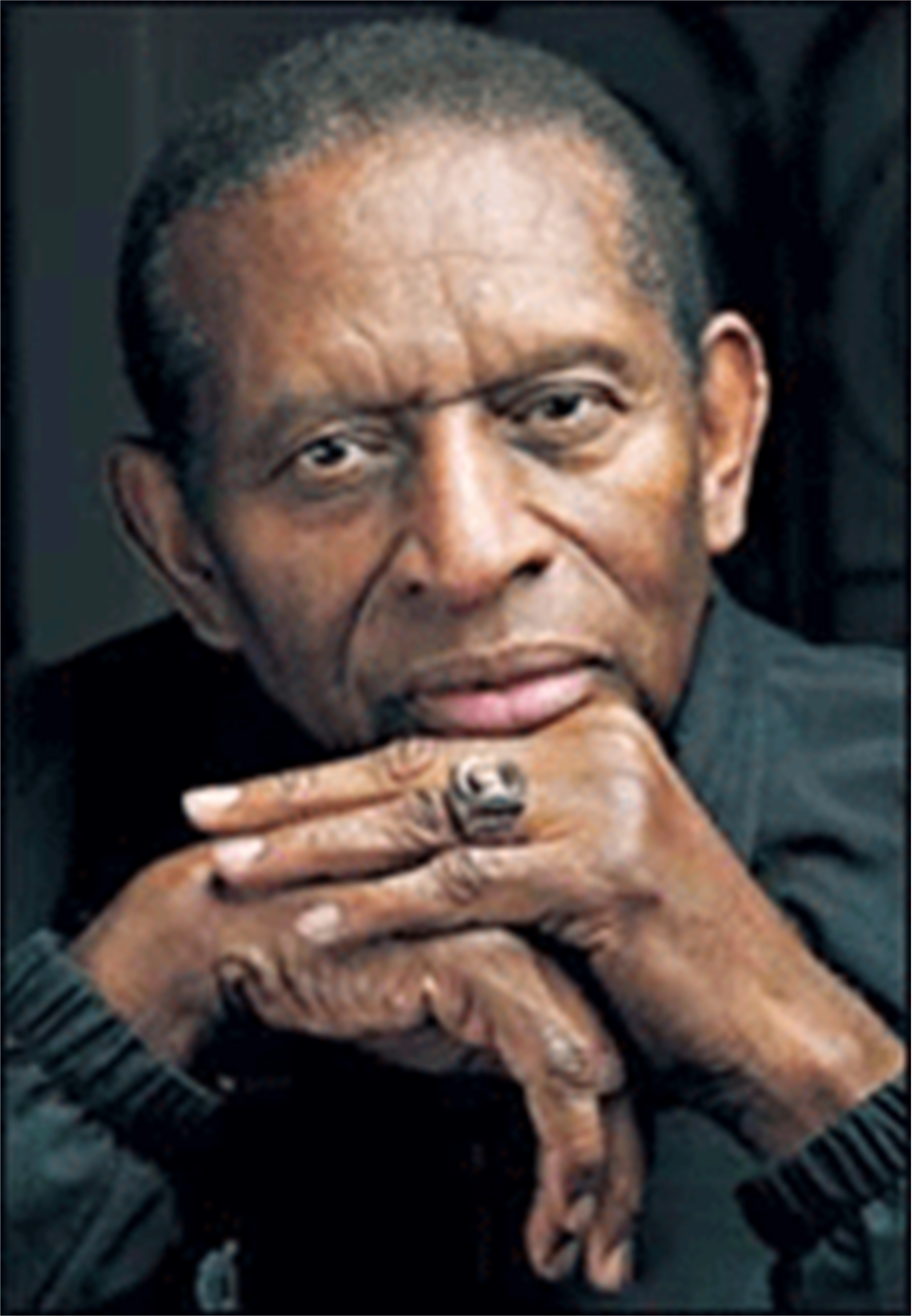

“You can’t compare what Jackie did to what I did!” says the 77-year-old Earl Lloyd, his deep, gravelly voice booming with emotion over the phone from his Tennessee home. “Jackie is my hero, and his path was so much rougher than mine that any comparisons are trite.”

But facts are facts. And the fact is, Lloyd broke the NBA’s color barrier when he took the floor for the Washington Capitals on October 31, 1950 against the Rochester Royals. One key difference between desegregation in basketball and baseball was that Lloyd had two fellow pioneers; the Celtics’ Chuck Cooper and the Knicks’ Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton, both of whom also joined the League in 1950. Lloyd is the last survivor of the trio; Cooper died in 1984, while Clifton passed in ’90.

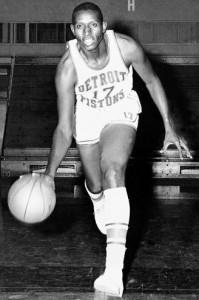

Lloyd, nicknamed “The Big Cat,” was picked by the Caps in the ninth round after a terrific career at West Virginia State. He played just seven games in Washington before being drafted again-into the Army. The Caps folded, but after a year in the service, Lloyd joined the Syracuse Nationals. In six seasons there, the 6-6, 220-pound forward set picks, grabbed boards and played tough D, and he averaged 10.2 ppg and 7.7 rpg in ’54-55 when he and teammate Jim Tucker became the first African-American players to win an NBA title. In ’58, he was traded to Detroit, where he played two more seasons. In ’68, he became the first African-American assistant coach with the Pistons, and he blazed more trails when he took over as Pistons’ head coach in 1970. After 40-plus years in Motown, Lloyd and his wife retired to Tennessee a couple of years ago. He was elected to the Hall of Fame as a contributor in 2003.

SLAM: Jackie Robinson was chosen specifically to break the color barrier. Were you three as well?

EL: I really have no idea-and I had no idea I was going to be drafted. In those days, if a team wanted to know something about a player they called the coach, and that was that. Looking back, the only indication that my coach may have known something is that at the end of the season, my teammate Bob Wilson and I were invited to travel with the Globetrotters for a week, but our coach was quite emphatic about not signing anything. I just accepted that without wondering why. I come from a time and place where people had welfare at heart, so that wasn’t hard to do.

Given the racial climate in Washington in 1950, I have a hard time believing the Capitals would have selected me if the Celtics had not drafted Chuck Cooper. Clearly, they were in no hurry to get to me. There’s nothing scientific about taking a guy in the ninth round; it’s a dartboard. I can’t think of another ninth-round pick in NBA history who made the team.

SLAM: Given that and your situation, did you think you had a chance when camp started?

EL: Not really. Playing in a real competitive conference [the then-mighty CIAA] gave me some confidence. In ’46, when I started college, most of the black talent found its way to my conference because the white schools were largely not available, and the few that were were only interested in the best players. I knew I could play, but I doubted myself when I arrived at camp. Of course I did. How can you not when you’ve been treated as inferior all your life? Most of the people who touched me during my formative years assured me about my worth. That’s nice, but then you get on the bus and see the sign, “For Coloreds,” and you keep walking to the back.

When I got to training camp, I saw guys I had read about, like Bill Sharman from UCLA and Dick Schnittker, the Player of the Year from Ohio State, and wondered if I belonged. Then your competitive juices kick in, and after three or four days, you realize that you do belong-and that is a very defining moment for a young black kid from a Southern state, whose supposed inferiority has been branded into his head since he was born. Everyone else is white and from bigger, more glamorous places, but you realize you can stand your own. Wow! It’s a new world from that day onward. And remember that from kindergarten to college graduation I had never had a white teammate or classmate. This was truly virgin territory for me.

SLAM: Most of the first black players were solid, tough role players rather than stars. Do you think that was intentional?

EL: The key to getting a job is you have to be good at what they need, and everyone needs rebounders and defenders and team players that are unselfish. There was always the fear that we were not smart enough to handle anything considered a skill position, and it was a long time before we got any shortstops in baseball and black centers, and quarterbacks were unknown until very recently. Of course, those rumors have been dashed on the rocks, but they were certainly alive and well in 1950.

SLAM: Was life on the road difficult?

SLAM: Was life on the road difficult?

EL: Well, it wasn’t a picnic, but the whole thing was a lot harder on Chuck Cooper. He was a dynamite guy who grew up in Pittsburgh and had never been denied access to a hotel or a dining room. This was nothing shocking to me – the folks in Virginia made my transition an awful lot easier. [Laughs] They got me ready to be called names and denied things, and they made the hecklers in NBA arenas look like amateurs. Those people in Virginia were very good at treating folks as less than human. The whole thing was less of an issue for Sweets, because he had toured the world with the ‘Trotters and nothing was going to surprise him. Plus, he was playing in New York, with everything you can think of at his fingertips.

SLAM: St. Louis is usually acknowledged as the worst city for black players at the time. Was that your experience?

EL: St. Louis was tough, but Indianapolis was the worst. In ’55, when we played the Fort Wayne Pistons for the championship, the American Bowling Congress booked their building, so they moved to Indianapolis. Those people were tough, man. Killers. But I realized that they only hurled vile names at you when you played well, and I worked through it by telling myself if I didn’t hear any names, I wasn’t playing hard enough.

SLAM: Why do you think Jackie Robinson had it so much worse than you?

EL: So many reasons! First of all, the public generally didn’t care about basketball, while baseball was the grand old game and he was considered an invader, a threat. I was lucky that we were under the radar and lucky that my first game was in Rochester, where high school teams had been integrated. No one thought twice about seeing black and white players together. I checked into the game and that was that. Most importantly, my teammates largely embraced me and other players ignored me at worst. They were trying to maim Jackie. Any black kid who needs inspiration should look up Jackie Robinson in the encyclopedia.

SLAM: So your teammates and coaches fully accepted you from the start?

EL: I can truthfully say this-in all my years in the NBA I never had a blatant racist comment directed at me by another player. Of course, there were some who would have preferred to not play against a black man, but they just played. That’s why I say it is a disservice to Jackie Robinson to compare me to him. I was lucky to end up in Syracuse, where I was welcomed and where I had great teammates. If you polled that team and asked who their favorite teammate was, half of them might say me. I really think they appreciated how I went about my business.

The stars were Dolph Schayes and Johnny “Red” Kerr, and they were both great guys. I have as much respect for Dolph on and off the court as anyone. To really appreciate him, you had to see him every day, because he was relentless. His work ethic had no peer. He was not fleet of foot or a great leaper, and he compensated by never, ever stopping or pulling back off the throttle. The guy that guarded him caught hold of hell.

SLAM: There was an unspoken quota of black players for years. At what point did race cease to be an issue in terms of making a roster?

SLAM: There was an unspoken quota of black players for years. At what point did race cease to be an issue in terms of making a roster?

EL: Even when there was a known quota, no one talked about it. No one ever said, “We can’t have but two blacks.” Who admits they’re racist? It was like a secret society, and it was understood. What really changed the landscape was the advent of the Players Association. Suddenly there was an organized manner to speak up against unfairness. I always laugh when people asked me if playing in the NBA was a goal of mine. How the hell you gonna plan a career where there’s no predecessor?

SLAM: You have participated in NBA rookie transitional programs. Do the players treat you with proper respect once they know who you are?

EL: Very much so. You should see the moment they find out who I am. They see this tall old black dude and figured you played, but then they introduce you and their eyes get wide. Then I got ‘em and I just let them know: I don’t want a thing from you, I want something for you-the very, very best. One kid said, “Mr. Lloyd, we owe you big time.” I said, “No one owes me anything. You owe the people coming up behind you to leave this thing a little better than you got it.”

It’s obvious that guys like Chuck and myself, we left it a better place.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!