Reflecting on 25 Years of Interviewing Gregg Allman

The surprising secret at the heart of Gregg Allman’s blues-rock music: He was really a folkie soul singer.

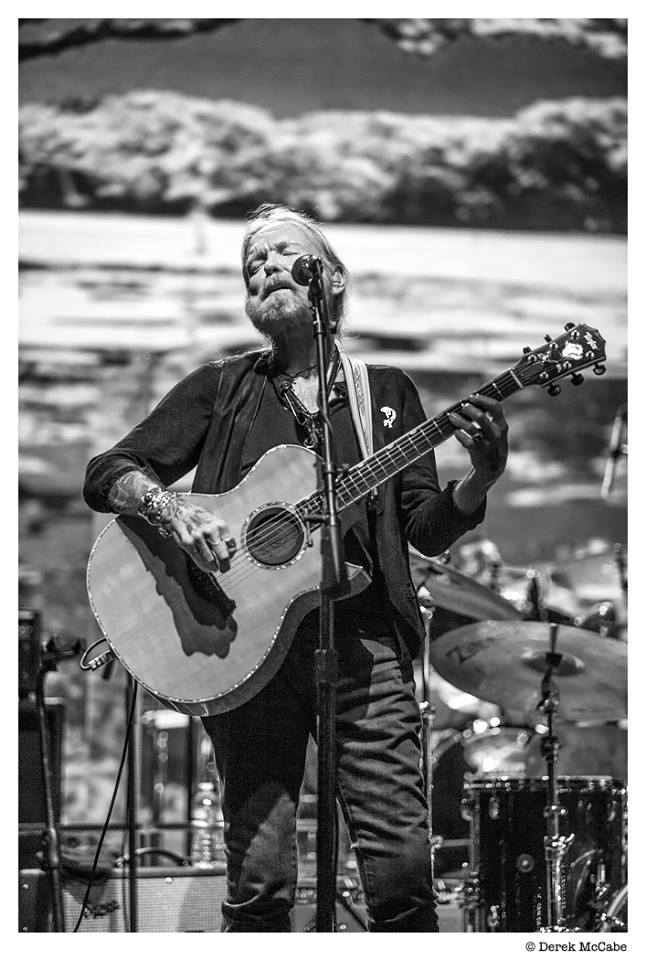

Photo – Derek McCabe

I wrote this personal reminiscence of Gregg Allman for Billboard. Re-posted here exactly as it ran.

The news of Gregg Allman’s death got me listening to his music on repeat. In that regard, today isn’t much different than any other day — just more so.

It’s hard to describe how much Gregg’s music has meant to me, as both a fan and a journalist who interviewed him dozens of times over 25 years. For me as for so many, Gregg and The Allman Brothers Band weren’t background music, and they weren’t a passing fancy. They were a touchstone to many of our lives’ happiest and saddest moments, and thus his loss resonates profoundly, like the loss of a family member.

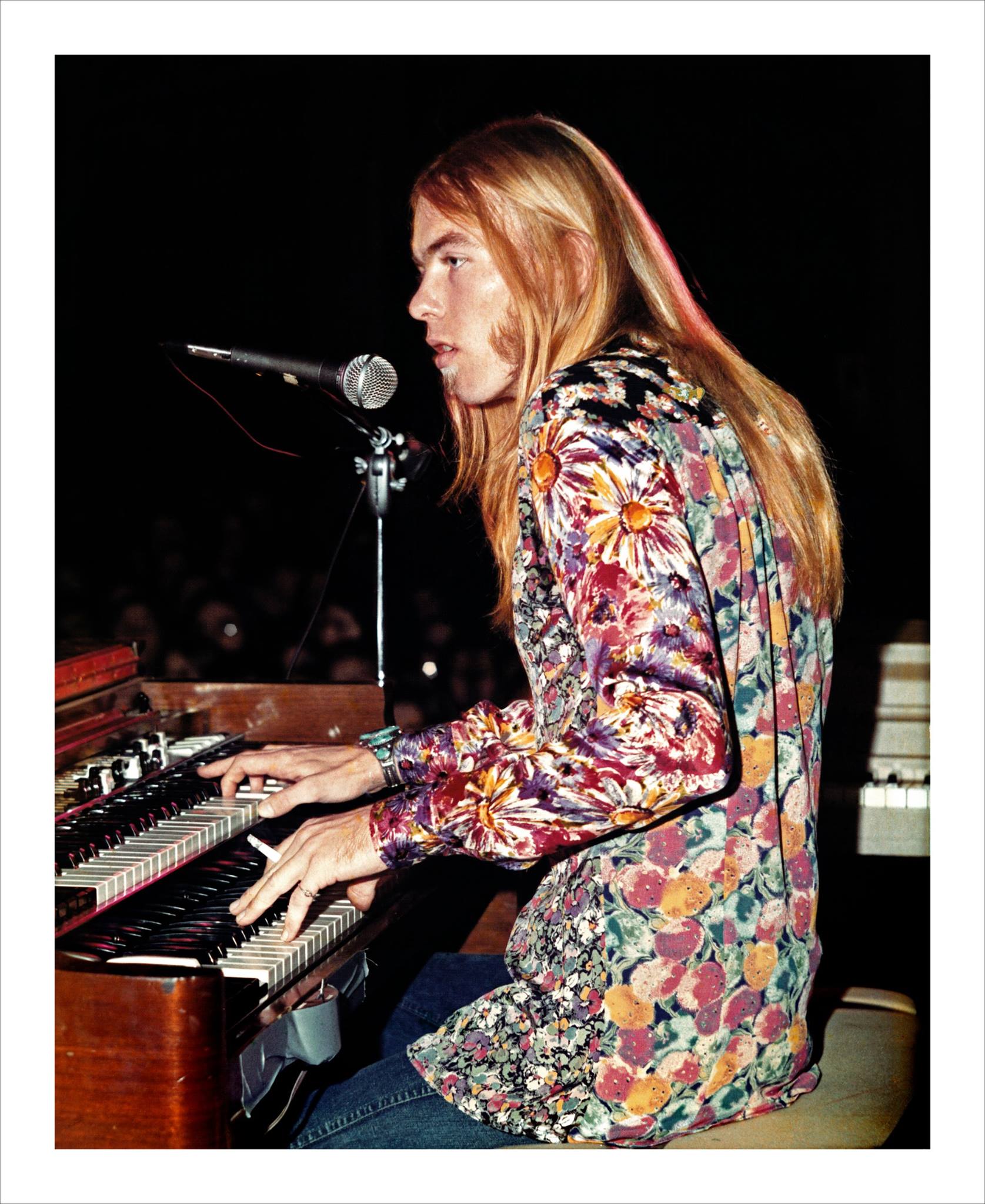

Gregg’s easy mixing of folk, blues and rock, genres that don’t usually go together is one of the hallmarks of his music. “A certain side of me has always viewed myself as a folk singer with a rock and roll band,” Gregg told me in 1995. “I developed that perspective when I lived in Los Angeles and saw people like Tim Buckley, Stephen Stills and Jackson Browne, who was my roommate for a while. All I had known was R&B and blues and these guys turned me on to a more folk-oriented approach and it’s always stuck with me, even if a lot of Allman Brothers fans never realized it.”

Most people don’t associate Gregg with California singer-songwriters but you could hear that love of folk rock in songs like “Midnight Rider” and “Melissa,” and in solo numbers like “Multi Colored Lady.” Gregg was not afraid to be vulnerable, to write and sing lyrics like “Come and Go Blues” that admitted to feeling lost, betrayed, heartbroken. Even “Whipping Post,” one of his most swaggering tunes, was rooted in a heartbreak and pain so profound that good Lord, he felt like he was dying. He sang the words night after night for 45 years, with a passion that connected with people because he embraced, rather than camouflaged, his pain. When he sang you heard his father being killed when Gregg was a toddler, and his father figure, big brother Duane, dying just before his vision of the Allman Brothers Band conquering the world came true, way back in 1971.

Photo – Sidney Smith

I interviewed Gregg dozens of times between 1990 and 2015 and I never quite knew what I would get. He could be thoughtful, funny and incisive, a fantastic storyteller and jovial presence, and he could be curt, just getting the job done. That’s not surprising for someone who spent a good chunk of his life picking up the phone to call reporters to advance a single show in Des Moines, Greenville or Irvine.

In 2013, I interviewed Gregg for the Wall Street Journal as he was promoting his memoir “My Cross to Bear.” It did not start out well. He was giving yes and no answers and I was scrambling to pull more out of him in our limited time. About ten minutes in, someone came to my front door and my little dog Meimei, resting at my feet, jumped up and started barking like a banshee. I was mortified, but Gregg was delighted.

“Hey!” he exclaimed with 1,000 times more enthusiasm than he had displayed prior. “You’ve got a little kitty, too? What is she?”

“A morkie, I think. She’s a rescue dog. What do you have?”

And then Gregg went off in a rapture about his two dogs, one of whom was also a morkie, and how much he spoiled them. I knew all this, having seen him with his beloved dogs over the years.

“Gregg, I actually use you as a defense whenever someone makes fun of me having a tiny dog,” I told him, quite truthfully. “If they say it’s not manly, I just go ‘Gregg Allman has two of them!’”

Photo – Kirk West

He chuckled. “I used to have giant dogs, even a St. Bernard once. I loved that dog! But you know who turned me onto little dogs? B.B. King. He told me, ‘You don’t know the love of a dog until you’ve had one who can sleep in the nook of your elbow.”

Now I had even better backup when someone made fun of my little pooch! B.B. King told Gregg Allman it was the way to go. Our interview resumed with new vigor and insight.

In 1997, I interviewed Gregg at 2 am in his Chicago hotel room after he played a solo gig at the Hard Rock Café. His then-wife Stacy and their two dogs were asleep behind us. It was a cover story for Guitar World Acoustic and I had brought an axe for him to demonstrate his finger-picked riff to “Come & Go Blues.” I handed it to him at the end of the interview, which had gone exceedingly well. It was the most relaxed, open conversation we ever had, by a long shot, which set the table for what came next.

He asked for a quarter and rounded off a couple of string ends. “You trying to take out my eye?” he inquired with a laugh. Then he re-tuned the guitar to an open tuning, took out a pouch with metal fingerpicks (which he put on) and showed me the riff, talking the whole time about how he was inspired to play in such a manner by Tim Buckley. Then he kept going, and he played and sang all of “Come & Go Blues.” Audience of one.

2009 – by Rayon Richards

It was an otherworldly experience, a moment where time and space were suspended and I was just right there. In that regard, it was just a heightened version of what millions experienced listening to Gregg for the last 50 years.

People talk about the concept of a musician having soul as if it were a phenomenon too complicated to grasp or explain. It is not. A performer has soul when he or she plays music because they feel compelled to do so, when he or she feels as if it is coming from another place and passing through them. Music has soul when it reminds listeners that they have one by stirring something within them, touching them somewhere deeper than their head. Music with soul doesn’t just entertain — it speaks. And it doesn’t just speak; it has something to say.

Gregg Allman had soul. Listening to him sing, you heard not just words or one-dimensional emotions, but determination, suffering, longing and love. This was in every note Gregg sang and played, because what he did is who he was. Gregg’s music was his life, his therapy, his means of expressing sadness and joy, of screaming in pain and gasping for breath. There was no wall between the artist and the art; everything he had went into his music, and the listeners understood that, even if they didn’t know it.

Alan Paul is the author of the New York Times best seller, One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band