Phathers and Sons: Trey Anastasio Meets Phil Lesh

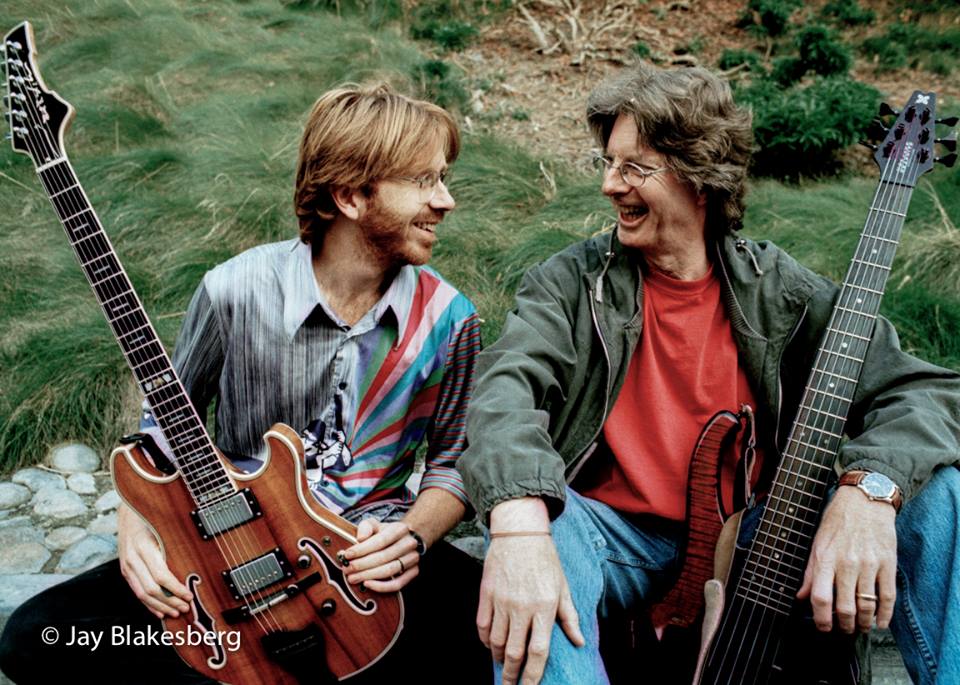

Photo – Jay Blakesberg at Shoreline

I compiled my best Grateful Dead-releated journalism in an Amazon Ebook, Reckoning: Conversations With the Grateful Dead. This interview with Trey Anastasio and Phil Lesh is one of the greatest, most unique stories in there. I wanted to share it with you. I was inspired to do so by my friend Jay Blakesberg posting the photo above on his Facebook page.

Phathers and Sons

The Grateful Dead’s Phil Lesh and Phish’s Trey Anastasio have only done one interview together. This is it.

The following interview – the only one that I know of with both Phil Lesh and Trey Anastasio – almost never happened. I started contacting Anastasio and Lesh in April, 1999, following the very first Phil and Friends shows, featuring Anastasio and his Phish bandmate Page McConnell. Trey quickly signed on and we targeted Phish’s two-night September appearance at Shoreline Ampitheatre in Lesh’s San Francisco Bay Area.

Phil was a lot harder to nail down. Phil and Friends was a new entity, lacking the normal structures of management and publicity. I got a name from someone as Phil’s contact and emailed with him about this interview for months. He thought it was a great idea and Phil and wife/manager Jill seemed to agree. But I couldn’t get any commitment and my contact finally told me that he wasn’t really a publicist; he was the father of a kid on Lesh’s son’s Little League team who had been helping Phil out. He was as frustrated as me.

Somehow, we pushed through all this; Lesh agreed to come to Shoreline at 5 pm on September 17, 1999, the second of two Phish shows. Phish sent a limo to pick up Phil and Jill and deliver them. I hung out at Shoreline all afternoon, growing excited. However, 5 pm came and went and no limo and no Lesh. Pre-cell phone, no one knew where he was or when he would arrive. They showed about an hour before showtime and Anastasio politely said he couldn’t do it so close to curtain, though I did nudge everyone into the photo with Jay Blakesberg that you see above.

Phish management kindly sat me in a box with Phil and Jill, and we had a nice chat. I recommended Jimmy Herring to him and while I’m sure I wasn’t alone in that, I like to think it played a part in the gig that would soon come the guitarist’s way. 9-17-99 was about to become a well-known day in Phish history, because by the second set Lesh had left our box and was walking on stage with the band. He played “You Enjoy Myself ” ,” even jumping on a trampoline, and stuck on stage for an extended jam, “Wolfman’s Brother” and “Cold Rain and Snow.” Warren Haynes joined Lesh and Phish for an encore of the Dead’s “Viola Lee Blues.”

It was an epic night of music, but I was crestfallen. I had come a long way for an interview that just didn’t happen. Both Lesh and Anastasio promised to see it through, but I doubted we would ever clear the logistical hurdles. I kept in touch with everyone and about seven months later, when Lesh and his Friends – now including Herring – played six nights at the Beacon Theatre in April, 2000, Anastasio traveled to New York. We rented a hotel room and sat down to talk the afternoon before a Lesh performance. Lesh had opted to keep touring with this band that spring and summer rather than join his ex-Deadmates in The Other Ones and was quite open about his preference to being in charge. Versions of the interview ran in Guitar World and Revolver magazines. It has never appeared in full before now.

•

Sitting across from each other in a New York hotel suite sipping coffee and San Pellegrino water, Phil Lesh and Trey Anastasio don’t look or sound anything like the once and future Kings of psychedelic rock. There is no day glo or tie dye to be seen. No dilated pupils. No muddled, Santana-esque raps about angelic visions.

With Central Park shimmering outside the picture window, the bespectacled pair looks more like father and son tourists preparing for a day on the town. At 60, the tall, angular Lesh is clean cut and fit-looking, remarkably so for someone less than two years removed from a life-saving liver transplant. The uninformed observer certainly wouldn’t guess that they were looking at Jerry Garcia’s right hand man. With his scraggly beard and unkempt hair, Anastasio is more disheveled, though there is still little to indicate that the Phish frontman is the shamanistic Pied Piper for a new generation of youth looking to turn on and tune in.

Appearances be damned, these two have been smack dab in the middle of some of the most exploratory rock and roll played for the last 35 years. In many ways, Anastasio’s Phish picked up where Lesh’s Dead left off following Garcia’s 1995 death, building a huge and rabidly dedicated following through hard touring, word of mouth and fanatical tape trading.

There is such a natural affinity between the bands that one might assume that their relationship stretches back for years, but it does not. Anastasio and Lesh first met two years ago, when Phil enlisted the guitarist and his bandmate, keyboardist Page McConnell, for three San Francisco performances. These shows, in April 99, were of particular significance because they marked Lesh’s remarkable recovery from his transplant. Lesh has since plunged headlong into the solo career he largely shunned during the Dead’s life, turning his back on his former Deadmates in The Other Ones to perform with his Phil and Friends.

“Phil faced down death and came out the other side and has basically decided to do exactly what he wants with no compromise,” says guitarist Warren Haynes, who has played with Lesh frequently and has become close with him. “That means a band which maintains the Dead’s improvisational quality, while also being more structured.”

Phish, meanwhile, has taken an extended hiatus, which will last at least one year, following over a decade of relentless touring. Just before the band’s final pre-break tour, Anastasio leapt at the opportunity to pick the brain of one of his musical heroes.

“I welcome any opportunity to sit and talk with Phil, which was one of my favorite things about playing with him,” says Anastasio. “Anyone who really cares about music can learn a lot from this man.”

TREY ANASTASIO: Phil, our experience playing with you last year was incredible for many reasons. But rehearsal was my favorite part. I really enjoyed the chance to spend so much time talking to you about music and the history of the band and just realizing that as legendary and great as the Dead was, it was also just a band with all the usual dramas and personalities. And on a simpler level, we rehearsed long and hard – eight hours a day! – and I love to do that.

PHIL LESH: I love to do it too, especially because we didn’t do much of it for an awful lot of years in the Grateful Dead.

ANASTASIO: But you must have done it for a while.

LESH: Yeah, and I loved it when we did. The first few years we played together all day, every day, no matter what, so we just got to know each other incredibly well. It trailed off in ’74 and after we took that break in ’75, that was pretty much it for rehearsal.

ANASTASIO: That’s really interesting. We’ve been slowing down on rehearsing a lot, though not really in a planned way.

LESH: Yeah. Life interferes with your schedule by intruding on that little hermetic environment. I think it’s an evolutionary process, where after a certain period of time you’ve done your woodshedding and you know each other well enough that maybe it’s not going to get much better. Maybe putting all that work and time into it isn’t going to really produce much in the way of results.

ALAN PAUL: Yet you seem happy to be rehearsing vigorously again. Was that ever a source of tension in the Dead?

LESH: Only subconsciously. The group mind was pretty much in accord in many ways, all the way through. I mean individuals have their own preferences, but the group mind really ruled, so after a while you give in to that. [laughs]

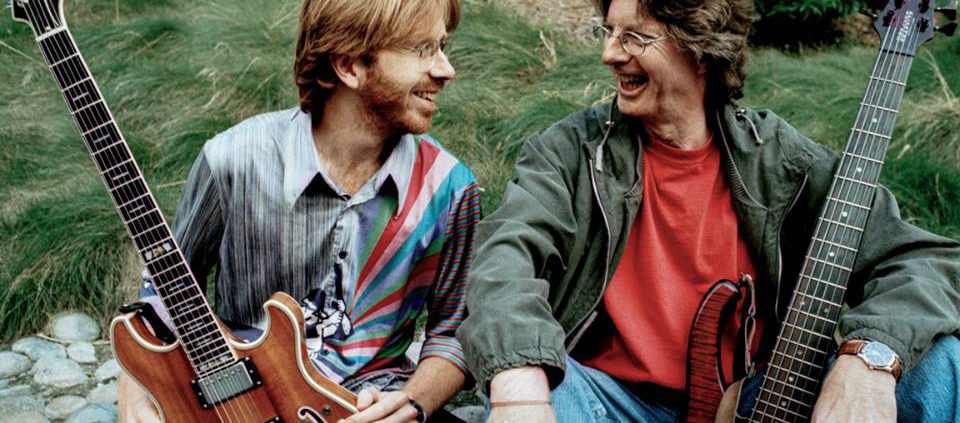

Almost 20 years later… Fare Thee Well. Photo – Jay Blakesberg

ANASTASIO: One of the things that will always put the Dead in a completely unique position is that you guys charted more new ground than any other rock band. You broke down boundaries and took influences from things like bluegrass and jazz at a time when there were no books written on how to do that. Whereas we could weigh the good and the bad, and decide what worked and what didn’t.

LESH: Well, you take what you need and you leave the rest. [laughs] Artists have always done that, so it’s not new and it’s not wrong.

ANASTASIO: Maybe it’s even more than that. I feel like there is an active second generation of bands right now and we can learn a lot from your successes and failures. I saw CSNY recently and spent the night talking to those guys afterwards. The first thing Graham said was, “Congratulations on your success. Don’t fuck it up.”

LESH: That sounds like something Nash would say. [laughs]

PAUL: So, what can you proactively do to make sure you don’t fuck it up?

ANASTASIO: I haven’t thought of anything specific and that’s what worries me. [laughs] Phil?

LESH: First, it has to be apparent that you’re fucking up, and that’s the hard part. Hindsight is easy. Musically, the quest never ends. Music is an infinite process, and that’s what holds the attraction. You’ll never get to the end of it, so you can never be bored with it. That’s why playing with so many different people after playing with the same ones for so long has been revelatory. I learn from every musician that comes through this band.

We have gone places that the Grateful Dead never went. My vision for the Dead was always group improvisation and movement and instrumental passages but not solos – not one person stepping out. Now this is my band and I can try to make it happen just as I always wanted, so it’s been liberating.

ANASTASIO: That brings up the concept of intent, which was the biggest thing I latched on to about the Dead. The intent behind a song always seemed to be about touching an emotion. It didn’t have anything to do with selling records. It didn’t seem like somebody sat down and tried to think out a hit song.

LESH: Oh, no. We couldn’t do it. In fact, we did try to write hit singles a few times, but it always came out sounding deformed. And that’s the way it goes when you try to do something like that.

PAUL: What is an example of such an attempt?

LESH: Actually, there’s only one instance to which I can concretely point, though I know there were others. It was when we were doing the follow up to our only hit single, “Touch of Grey” and the album In the Dark. We were recording Built to Last and we really thought “Foolish Heart” was going to be the next big thing, and worked on it with that in mind. But we did it in the weirdest way. We recorded a basic track, then everybody erased their parts and overdubbed.

ANASTASIO: Really? One at a time? Wow. Did you leave the drums?

LESH: Actually, I think we made the drummer play along with the other track. It was the most bass-ackwards kind of way to make a record. I don’t really know what we were thinking. It would be very hard to explain. And it just goes back to the fact that the payoff for the Grateful Dead was playing for people. We were a live band.

PAUL: For both of your bands, the concert experience is even bigger than the music.

LESH: Absolutely. The shows create a little sanctuary. You know that the world is temporarily reduced to this group of like-minded people. And it’s the same urge that brings people together in any situation, be it a poetry reading, a concert hall or a coffee shop. People have gathered together to hear music for as long as there have been people. We’re up there making music and singing songs, like telling stories around a campfire. That’s something both our bands share. Getting together like that is something as old as humans, and there’s a reason people have always done it.

PAUL: Fan tape trading has played an important role in the success of both the Grateful Dead and Phish. The notion of allowing — and even encouraging — people to tape concerts hardly raises eyebrow now, but when the Dead began doing so, the larger music world was shocked.

LESH: The tradition of taping Dead shows started in a very humble way. A fan simply asked permission to record one of our performances, and Jerry [Garcia] said, “After we play it, we’re done with it. Let them have it.” And everybody agreed. The group mind spoke through Jerry, and it turns out to have been the smartest move we ever made.

ANASTASIO: We did it from the start but again we basically learned from the Dead’s example and encouraged taping from the start. In our early days, we were able to tour the country with no record label solely on the strength of word-of-mouth and tape trading. That’s just one example of how much easier things have been for us, thanks to the Dead.

PAUL: What’s your view of fans downloading music via Napster and other Internet sites?

ANASTASIO: It gets more complicated when people download studio albums without paying for them, but I don’t believe you can stop it. My only answer is, I hope that the Internet spawns a new morality — one where people begin to develop a deeper respect for artists and their work, and voluntarily pay when they download music.

PAUL: Phil, as someone who lived through the Sixties—a time when many people dreamed of a new morality—do you think that’ Trey might someday have his dream become reality?

LESH: I’m not sure; it all depends on your ability to create a strong personal bond. Personally, I’m skeptical because I find communicating via the Internet to be distancing. I hope, however, that the ‘Net continues to be unregulated. We’ve seen the good it’s done in repressive regimes like China or Kosovo where people have been able to receive uncensored information by fax and the computer.

ANASTASIO: I don’t know if it’s going to happen, because it may well be co-opted by commerce, but the potential is there to put the power in the hands of the people. For people to instantaneously communicate with one another from anywhere.

LESH: That’s a righteous prediction, and it’s going to happen. The ecommerce is what’s going to drive the creation of the bandwidth and network that will give us instantaneous, lightning fast download of any artistic material, and media.

ANASTASIO: I’m a little more optimistic about Internet culture. The ‘Net has played a huge role in creating a community for Phish fans. One hundred thousand people came to see us play in a Florida swamp last New Year’s Eve, and as far as I know we didn’t buy a single word of advertising. Word spread on the Internet, and it sold out in advance.

But what was really incredible was the level of respect our audience had for the event. For example, there was no garbage left on the site. People knew from talking online that the show was held on an Indian reservation, so they cleaned up after themselves. At the end of the event the people had neatly stacked over 90 tons of recyclable trash. And the whole thing was done without involving the media in any way.

PAUL: Are either of you nostalgic for the activism of the Sixties?

ANASTASIO: I find it sad that when people reflect on that decade they tend to focus on things like pot and tie-dyes instead of the ideas that were being discussed. It was a time when people believed in change. Or so it seems from the perspective of someone who was three years old in 1967. Am I right, Phil?

LESH: Oh, yes. There were a lot of utopian dreams, and they were the foundation of everything we did. Everybody thought we really had a handle on things.

PAUL: It is widely believed that one of the things that undermined those dreams was hedonistic excess. Do either of you feel any dismay that drugs are a big part of the listening experience for many of your fans?

ANASTASIO: I certainly feel a responsibility for the overall safety and well being of everyone at our shows, but I don’t think we can control their actions. We can’t force them to be clean any more than we can force them to drive intelligently The decision to use a substance is a personal choice, and while I have had some positive experiences with drugs, I would never encourage anyone to use them. Phil and I both have kids, so I think we understand the danger in suggesting anything like that.

LESH: People have always tried to break down the barriers that hold them within their physical form. No matter what time we live in, or what legislation is enacted, people will continue to do this. Some of these drugs are sacraments, which open you up. Others are not. People who lie around and use hedonistic drugs are not the same people who do psychedelic drugs seeking to connect with a higher consciousness. It’s a basic human drive to know that there’s more to the world than meets the eye. That’s what religion is all about. Psychedelics are really a shortcut — ultimately, music alone can take you there — but I don’t think that makes the experience any less real.

ANASTASIO: That’s very true. Psychedelics didn’t ruin me. I’m a productive member of society and a good father of two great kids. The first time I ever took acid was at a Dead show in New Haven. It really did change my life and open up my mind; it was a pivotal experience. That doesn’t make me want to do it every day, but I certainly have no regrets because it really woke something up in me.

LESH: At various stages in your life, there are things that wake you up. My first encounter with music was like that. It’s why I became a musician, and it continues to this day.

PAUL: Because of the cult-like nature of your respective followings, both of you could easily release albums on-line exclusively. How does being on a major label benefit you?

ANASTASIO: Limos to drive you around when you come to New York, as well as free coffee and a conference room to do interviews in. Without them, you have to pay for the coffee. And, of course, they give us plenty of aggravation. But, to be honest, we have a good balance right now. We’re allowed to put out live albums via our newsletter or the Internet, and still put out albums on Elektra, so we’re happy.

LESH: The majors sure were sorry they signed us. We never paid off for them, and we did like to spend the money. I think we knew all along that the Dead was a band that played for the people. That was the payoff for us. The studio was a diversion, and we were never really good at it.

ANASTASIO: Oh, I disagree.

PAUL: What’s your favorite Dead studio album, Trey?

ANASTASIO: I have two favorite tracks: “Casey Jones” and “Shakedown” Street,” both of which have great, very unique basslines. I heard “Shakedown” on my car radio the other day and was overcome with how unique sounding it actually is.

LESH: When you hear, the Grateful Dead within a medley of radio songs, it sounds so different. It doesn’t sound like a radio song at all. We never figured out how to do that through 30 years. I still don’t understand how to do it. The few times we actually tried to make a hit single, it came out sounding rather deformed, not surprisingly.

PAUL: Well, that’s not quite true. After 20 years The Dead had a hit single in 1987 with “A Touch of Grey,” which paved the way for the band’s late-Eighties revival. Were you surprised by the song’s success, and how did it affect the band?

LESH: Yes, we were completely surprised, and its effects were dramatic. It brought in a number of young people who didn’t really have a feel for the scene and the ethos surrounding it, which was considerable after two decades. We were thrilled with the interest in the band, but it just stood everything on its head. More people wanted to see us, so we had to play larger venues. Playing in front of larger crowds resulted in a loss of intimacy, and for me the experience was all downhill from there. Of course, the decline might have happened anyhow, because after 22 years we were struggling creatively. We were just out there hacking away at it, and the new success actually made it easier to keep going, because it gave us more resources.

But it also inflated the whole organization. We had to fulfill all these obligations just to pay the bills, and that meant three tours a year plus weekends, and no chance to ever take a breather and get it together. This inflation seems to be the inevitable course of success.

ANASTASIO: Do you think a hit single would harm us – and our community? Some people think so, and it’s a big topic of discussion in our camp.

LESH: From my experience, I would have to say yes.

ANASTASIO: But, the thing is, I like hit singles! I always give people who can write them incredible amounts of credit.

LESH: Absolutely. In many ways, a hit single is the ultimate example of tapping into the zeitgeist of the time. They really are strokes of inspiration, because they have to be composed well before the moment they hit public consciousness. A great song that reflects what the masses are thinking and feeling is a function of true precognition. I also think a three-minute single may well be the perfect metaphor for this moment in history where everything changes so rapidly.

PAUL: Trey, in your mind what made the Dead so musically unique?

ANASTASIO: Many things. First, their relaxed quality. Back in the Eighties, a Dead show might’ve seemed kind of slow, but when you really paid attention to what was going on, you discovered a conversational quality that was totally unique. Their jams would make the whole arena resonate — almost like the building was becoming an instrument. There was a sensitivity that just does not happen at arena shows. You could sense that the Dead not only listened to each other, but that they were actually sensitive to the entire environment, which brought everyone in the room in the picture.

Also, I was immediately and completely blown away by Jerry’s guitar playing and singing. I really have come to deeply miss that feeling, when he would start to sing a song and the hair would stand up on the back of your neck. He would sing one line and the whole place would just melt. It was magic, and as the years go by it starts to sink in that that’s never going to happen again. It was so bristling with depth that you simultaneously wanted to cry and crack up laughing.

LESH: Oh yeah, that was there from the beginning. Being in a band with Jerry was cosmic. It always felt like destiny. There was just an overwhelming sense of rightness for everybody involved. And, ultimately, I think we all reinforced each other. The heart was distributed between us.

ANASTASIO: Growing up in suburban New Jersey, with the mall as the center of everything, I often wondered, “What does life have to offer me?” All I could see was consumerism, but the concept that buying things was going to make me happy seemed hollow and meaningless. School offered nothing, and even most music seemed horrible. Music was supposed to be all about spirituality—its history is intertwined with weddings, births and funerals — but there was nothing. And then I saw the Dead, and I immediately understood that they were trying to communicate real, human emotions instead of fake, consumer emotions. And I just threw my arms around them and embraced their music.

PAUL: Phil, you have done a lot of touring and even jamming with Bob Dylan. What is your perspective on what makes him so great?

LESH: Every generation throws up a few real masters and in our generation it’s probably the Beatles, Coltrane, Picasso and Dylan. He’s a poet, an artist and a hero. “Subterranean Homesick Blues” was the first thing I heard on the radio that really knocked me out. Hearing Bob Dylan on AM radio was a reminder that anything is possible. Dylan going electric was an absolute door opener. More so than the Beatles, whom I didn’t really like at first.

There was one point in ’64 where you could walk the streets of [San Francisco’s] Haight-Ashbury and hear Bringing It All Back Home coming out of virtually every window. And it had a profound influence on people while also completely altering the prevailing concept about the level to which you could take songwriting. It changed everything.

PAUL: In Phil and Friends you have now played with three Allman Brothers Band guitarists — Warren Haynes, Jimmy Herring and Derek Trucks. In many ways there has always seemed to be a simpatico feeling between the Dead and the Allmans, two bands that approached similar ideas from very different perspectives.

LESH: Exactly. As musicians those guys have always had that same kind of open mind and willingness to go for the brass ring even at the risk of falling flat on their faces, which is very endearing to me. And it doesn’t surprise me that they could come up with the idea in Georgia while we were doing so in California. There are times when things are in the air. Revolution in the air, as Dylan said. And where you’re from just sort of determines your approach to the same basic problem or aspect or way of looking at things. And it’s definitely a major way of looking at music. And at life, if you like.

Trey, I’m curious about the relationship between improvisation and composition in Phish’s music.

ANASTASIO: I think a lot more of it composed than people seem to realize.

LESH: At your show at Shoreline, I couldn’t tell what was composed and what wasn’t, which I consider an ideal blend, something I hear in the music of Branford Marsalis. What are the proportions of each, and how do you determine what’s going to be improvised?

ANASTASIO: I used to really write a lot out, so some of the earlier tunes are fully charted — the drum parts, bass lines, guitar and keyboard fills, everything. And in our earlier years we did all these atonal fugues and other things which had to be played just so. Over the years we’ve done less of that and opened things up a bit but I still think it’s safe to say that more is composed than people imagine. We have a song called “Billy Breathes”…

LESH: Right. I know it.

ANASTASIO: Well, that outro that sounds like a jam is actually composed. The solo and everything is actually written out on paper, though when we play it live we will break away from it.

LESH: Ok. My question was actually about the live performance. It’s an interesting mix.

ANASTASIO: You have a compositional background, Phil. Are you writing out charts with this band?

LESH: No. I’m just encouraging active listening and “composing” on the fly. We move rapidly from one song to another, and oftentimes in the middle of an improvisation, someone will quote another song, which we sometimes will then actually play. People seem to think those moves are planned, but they are not. My experience is that if you have the right group of people and allow them to find such conjunctions on their own, they end up being beyond anything I could have thought up myself. It’s worth being forced to grope through darkness to find those magical moments. In fact, I consider that groping to be a big part of the art.

Thanks for digging this one out and sharing. Two great musicians. There’ll be nothing ever again like the energy vibe of those P&Ph shows at the Warfield in ’99.

TREY WAS GOD IN 1990 THRU 99