The 45th Anniversary of Eat A Peach

Today is the 45th anniversary of the release of Eat A Peach, the album that first hooked me on the Allman Brothers Band. In honor of this, I offer you this edited excerpt from One Way Out: The Inside History of the Allman Brothers Band about the making of this landmark album. You can buy the paperback by clicking the link above, or order a signed copy of hardcover or paper by clicking here.

***

After the release of At Fillmore East and before it’s gold certification, the band entered Miami’s Criteria Studios with Dowd to work on their third studio album, which they had begun the previous month by laying down the initial tracks for “Blue Sky,” Betts’ sweet, country-tinged tune, which would be his first vocal with the band.

TOM DOWD: They only had a few songs ready to track and we never wrote in the studio. That was one way we saved money on studio time.

DICKEY BETTS: I wrote “Blue Sky” for my then-wife Sandy Blue Sky, who was Native American, but once I got into the song I realized how nice it would be to keep the vernaculars — he and she — out and make it like you’re thinking of the spirit, like I was giving thanks for a beautiful day. I think that made it broader and more relatable to anyone and everyone. That was a bad marriage but it led to a good song.

BUTCH TRUCKS: Dickey wanted Gregg to sing “Blue Sky” and Duane just got all over him. He said, “Man, this is your song and it sounds like you and you need to sing it.” It was Dickey just starting to sprout his wings as a singer.

The band worked on three songs — “Blue Sky,” an instrumental track tentatively called “The Road to Calico,” which would eventually have vocals added and become “Stand Back,” and “Little Martha.” The latter, a sweet, lilting Dobro duet, was the only composition ever credited to Duane Allman.

BETTS: Duane and I played acoustics together all the time backstage and in hotel rooms and buses. Duane usually had his Dobro, I had a Martin and Berry had a Gibson Hummingbird. The three of us spent plenty of time sitting around playing blues — Duane loved Lightnin’ Hopkins and we both loved Robert Johnson and Willie McTell. We also worked out things for our own songs. “Little Martha” was not all typical of what we played — it sounded more like something I might do, really — but he had shown us pieces of it for years, so it wasn’t a shock.

ALLMAN: My brother loved playing that kind of stuff, and I have to think there would have been more music coming out of him. He put “Little Martha” together piece by piece.

BETTS: The song is played in straight E. I played the low third and Duane played the higher third. He wrote that song for his girlfriend Dixie; she’s “Martha.”

Betts’ insistence on this title is at odds with what most others believe; that “Little Martha” is named in honor of Martha Ellis, a 12-year-old girl buried in Rose Hill, with an eerie late 19th century statue atop her grave.

TRUCKS: Until that time I had always been sort of the lead drummer in the studio, but “Stand Back” was a perfect song for Jaimoe because it was this funky r&b style he’s so good at and I said, “You play the drums on this. I’m not even going to play.” Jaimoe took the lead.

JAIMOE: “Lead drums?” I don’t really call it that. What I was playing fit the song more than the kind of feel that Butch plays. It was a simple, funk thing that fit what I was doing. There’s a lot of things that maybe he shouldn’t have played on, but that kind of decision wasn’t made. There’s always a positive and a negative to everything you do, so what’s the sense of even bringing this kind of stuff up? Well, it might be interesting for people listening to us to know these things, just like Miles Davis or Elvis Presley, or anyone else people listen to and care about.

Photo – Twiggs Lyndon

NOTE: There is no easy way to summarize the next chapters of the book, or of the band’s history, but here goes. After finishing those three songs in about a week, they took a break and returned to the road, ending a short run of shows on October 17, 1971 at the Painter’s Mill Music Fair in Owings Mill, Maryland. Then, with most of the group struggling with heroin addictions, Duane, Oakley, Red Dog and Kim Payne checked into rehab in Buffalo, NY.

Duane returned to Macon on October 28, 1971 after a stopover in New York City. The next day, he was killed in a motorcycle crash. The details of the Buffalo rehab, the New York visit, the last day in Macon and the horror, shock and pain of Duane’s death are all important, and if you don’t know them well, I urge you to read up in One Way Out. For the purpose of our Eat A Peach story, let’s say that no one knew what would come next and it was equally impossible to imagine the band continuing without Duane and ending right there.

The band took a short hiatus before regrouping, gravitating back towards each other and immersion in their work. They committed to fulfilling previously scheduled dates in New York. Their first appearance without their leader was at CW Post College in Long Island on November 22, 1971; it was exactly three weeks after Duane’s funeral. In December they returned to Miami to work on the album. Our story continues there.

The band recorded four more outstanding tracks with Dowd, including “Melissa,” Betts’ instrumental “Les Brers In A Minor” and “Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More,” Gregg’s defiant response to his brother’s passing.

ALLMAN: I wrote “Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More” for my brother right away. It was the only thing I knew how to do right then.

TRUCKS: Of course, the music we recorded was all about Duane. Gregg wrote “Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More” and that was obviously about how to deal with this tragedy, but I think “Les Brers in A Minor” is about Duane just as much. We did everything we could to try and fill the gap and “Les Brers” was Dickey’s response — starting with the title, which is bad French for “less brothers.”

BETTS: When I wrote “Les Brers” everyone kept saying they had heard it before, but no one could figure out where, including me. But it’s in my solo on “Whipping Post” from one night. It was just a lick I was playing in there, and years later it showed up in a bootleg, which was kind of amazing. I mean, none of us knew where it came from until that tape surfaced years later. It just sounded familiar.

TRUCKS: We were all putting more into it, trying so hard to make it as good as it would have been with Duane. We knew our driving force, our soul, the guy that set us all on fire, wasn’t there and we had to do something for him. That really gave everybody a lot of motivation. It was incredibly emotional.

BETTS: It was difficult to suddenly have to play slide and I put in some time to get my part down for “Ain’t Wasting Time No More.” I’ve always enjoyed playing acoustic slide and would even often play it with Duane; when the two of us played acoustic blues I was often the one with the slide, but I never cared as much for playing electric slide.

The band also recorded “Melissa,” a song Gregg had written in 1967 — he says it is his first tune he ever considered a keeper after several hundred — but had never recorded.

ALLMAN: When we were finishing Eat a Peach, we needed some more songs and I knew my brother loved “Melissa.” I had never really shown it to the band. I thought it was too soft for the Allman Brothers and was sort of saving it for a solo record I figured I’d eventually do.

The double album Eat A Peach was completed with three live songs: “One Way Out” from the June 27, 1971 final concert at the Fillmore East, and two songs recording during the March At Fillmore East performances: “Trouble No More” – the Muddy Waters track that had been the first song Gregg sang with the band – and the epic, 33-minute “Mountain Jam.” The latter, which took up both sides of a vinyl album, had been an evolving staple of their performances almost since the beginning.

DOWD: When we recorded At Fillmore East, we ended up with almost a whole other album worth of good material, and we used [two] tracks on Eat A Peach. Again, there was no overdubbing.

ALLMAN: We always planned on having “Mountain Jam” on this album. That’s why you hear the first notes of the song as “Whipping Post” ends on At Fillmore East.

TRUCKS: That “Mountain Jam” is only on there because it’s the only version we had on multi-track tape and it was such a signature song of the band with Duane that we simply had to have it on a record. We played it many times so much better, but better a relatively mediocre version than nothing at all.

BETTS: That was probably the worst version of “Mountain Jam” we ever played. When we were recording live, we really were still focused on the crowd rather than the recording.

With recording done, the album had to be mixed. Dowd started the process, but the album had run over and he had other commitments, so Sandlin was called to Miami.

SANDLIN: I think Tom had to work with Crosby Still and Nash. I went down to Miami the last day Tom was still working on it, and sat with him, and he showed me what he was doing and discussed some aspects of recording. As I mixed songs like “Blue Sky,” I knew, of course, that I was listening to the last things that Duane ever played and there was just such a mix of beauty and sadness, knowing there’s not going to be any more from him.

I was very proud of my work on Eat A Peach but really pissed because I did not receive credit, only a “special thanks.” It was the first platinum record I’d ever worked on and it meant a lot to me, so that felt like a slap.

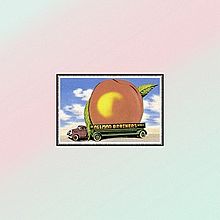

TRUCKS: After we were all done and the album was being finalized, I walked into Phil’s office and they showed me the beautiful artwork, with this title on it: The Kind We Grow in Dixie. I said, “The artwork is incredible, but that title sucks!”

DAVID POWELL, artist, partner in Wonder Graphics, which designed the Eat A Peach cover: I saw a couple of old postcards in a drugstore in Athens, GA, which were part of a series called “The Kind We Grow in Dixie”; one had the peach on a truck and one had the watermelon on the rail car. I thought they were perfect for an Allman Brothers album so I pasted them up and bought cans of pink and baby blue Krylon spray paint and created a matted area to make the cards on a 12” x 24” LP cover. I envisioned this as an early-morning-sky feel.

DAVID POWELL, artist, partner in Wonder Graphics, which designed the Eat A Peach cover: I saw a couple of old postcards in a drugstore in Athens, GA, which were part of a series called “The Kind We Grow in Dixie”; one had the peach on a truck and one had the watermelon on the rail car. I thought they were perfect for an Allman Brothers album so I pasted them up and bought cans of pink and baby blue Krylon spray paint and created a matted area to make the cards on a 12” x 24” LP cover. I envisioned this as an early-morning-sky feel.

Then I hand-lettered the Allman Brothers name and photographed it with a little Kodak camera and had it developed at the drugstore, then cut the letters out and pasted them on the side of the truck, under the peach. Duane was still alive and the album had not been titled. We figured we’d go back and add that.

TRUCKS: Duane didn’t like to give simple answers so when someone asked him about the revolution, he said, “There ain’t no revolution. It’s all evolution.” Then he paused and said, “Every time I go South, I eat a peach for peace.” That stuck out to me, so I told Phil, “Call this thing Eat a Peach for Peace,” which they shortened to Eat A Peach.

It didn’t occur to me until decades later that Duane’s comment was a reference to T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” though I knew Duane was a big fan. I was reading Prufrock and came across the reference to eating a peach and was blown away. The symbolism is obvious. Prufrock was totally anal and didn’t want to do anything that would get messy and there’s nothing messier than eating a peach. Duane would have loved that metaphor.

POWELL: The cover was kind of a new approach, a soft sell, because it did not say the name of the album – and the name of the band was just in tiny letters. We left that to a sticker on the shrink-wrap. When we showed it to someone at the label, he said, “They are so hot right now, they could sell it in a brown paper bag.”

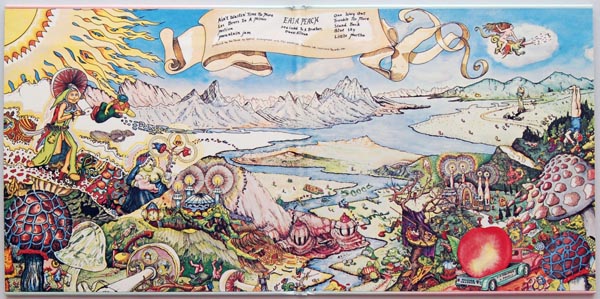

The double album opened up as a gatefold filled with another Wonder Graphics piece of art; an entire universe that seemed to promise some kind of psychedelic paradise. It told a story of happy, mystical brotherhood that was receding ever further into fantasy as the band grappled with the tragedy of Duane’s death.

POWELL: That was really a cooperative venture between Jim [Flournoy Holmes] and I, completed with almost no planning or discussion. We were working on a large piece of illustration board, on a one-to-one scale – it was the size of the actual spread – and we just started drawing, with Jim’s work primarily on the left and mine on the right. This work was profoundly influenced by [Hieronymous] Bosch.

The whole thing was done over the course of one day while we were in Vero Beach, Florida. While one of us was drawing or painting, the other was out swimming in the ocean. We swapped off this way with virtually no conversation about the drawing, just fluid tradeoffs.