RIP Hal Greer – my Slam feature on

RIP Hal Greer. I profiled him in Slam in 2003. I have not updated the file. All information was accurate as of then. Complete Washington Post obit here.

*

It’s time for a pop quiz, so put down your book and pick up your pencil. This won’t take long. It’s a one-question test, one which should a breeze for a hoopshead such as yourself.

- Who is the leading scorer in Philadelphia 76ers franchise history?

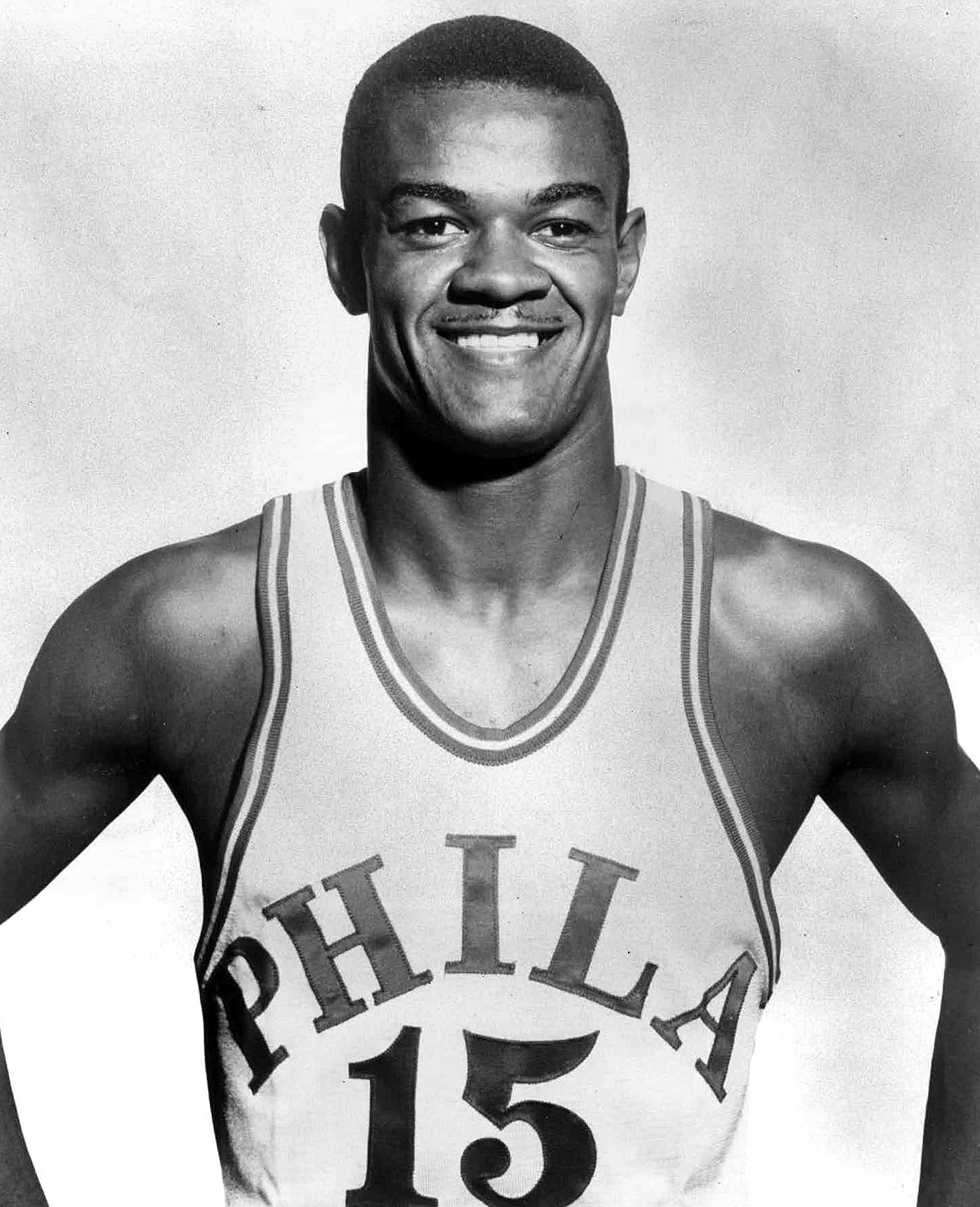

Julius Erving? Try again. Moses Malone? He only played five years in Philly, kid. AI is a little more than halfway there, so maybe some day.. Billy Cunningham? He’s in the Hall of Fame, but he’s not even close. Wilt the Stilt was the most dominant player ever but he only spent three and a half years on the Sixers, so he’s not the man. Sir Charles scored a bundle in the city of Brotherly Love, but he departed too soon to top the heap. The answers, lady and gentleman is… Harold Everett “Hal” Greer. In fact, only 20 guys in the history of the NBA have scored more points than Hal, but don’t feel bad if you didn’t know. You’re not alone.

“Hal Greer is one of those guys who has gotten lost in the shuffle,” says Jerry West, a fellow Hall of Famer who had many memorable matchups against Greer. “That’s not right, because he was fantastic. Hal was very serious – there was no frivolity in his game – and very quiet. And he played with Wilt, which is enough to obscure anyone’s accomplishments.”

It’s not fair to call Greer forgotten — he was elected to the HOF in 81 and named one of the League’s 50 Greatest Players in 96 and one of the main drives in Huntington, West Virginia, where he both grew up and starred at Marshall, is named after him. But considering the scope of his accomplishments Greer is definitely more obscure to even the most devoted fan than he should be. Consider that in 15 years with the 76ers and their precursors, the Syracuse Nationals, Greer was the model of consistency, steely will and complete, passionate dedication to playing winning, team basketball. He scored 21,586 points – exactly 205 less than Larry Bird, who is just above him on the all–time list — dished out 4,540 assists and scored 22.1 ppg (two less than Wilt) for the Sixers’ 67 title team, which went 68-13 and is still considered one of the best squads of all time. And Greer stepped up his game in the postseason, dropping 27.7 ppg.

“Harold was small but quick and extremely smart and tenacious,” says Dolph Schayes, who was Greer’s teammate from 58-63 and his coach from 63-66 and who is also in the Hall of Fame. “And he was probably the best mid-range shooter in the history of the game.”

You can’t talk to anyone who saw Greer play without hearing the words “midrange jumper” within three minutes. Speaking on the phone from his Arizona home, Greer, 67, laughs when asked how he developed that deadly 15-20 foot shot.

“I think it had to do with learning to play at home on a basket attached to a barn, which meant that I couldn’t drive, so I was always shooting,” he says. “And I spent countless days and nights alone in the Marshall gym running back and forth from one free throw line to the other, stopping and shooting. I had my own key and I’d go in there, turn the lights on and practice my jump shot for hours.”

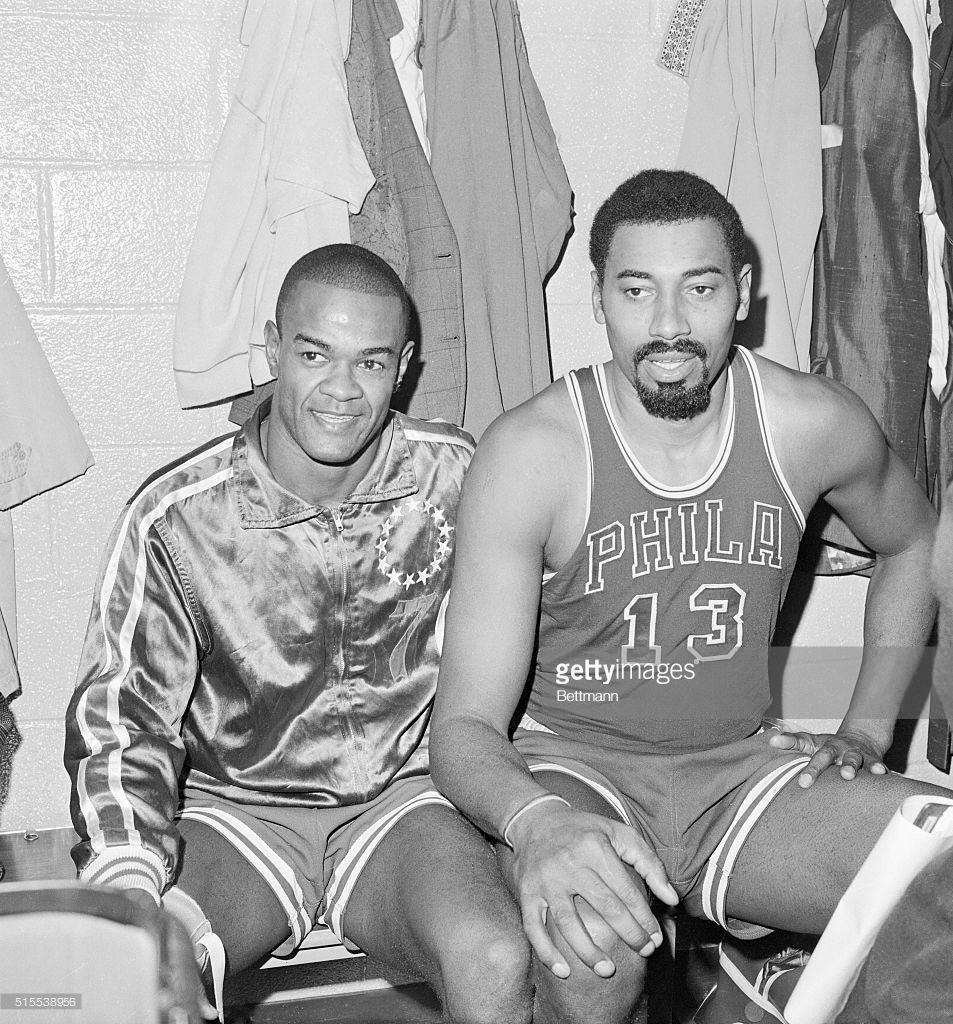

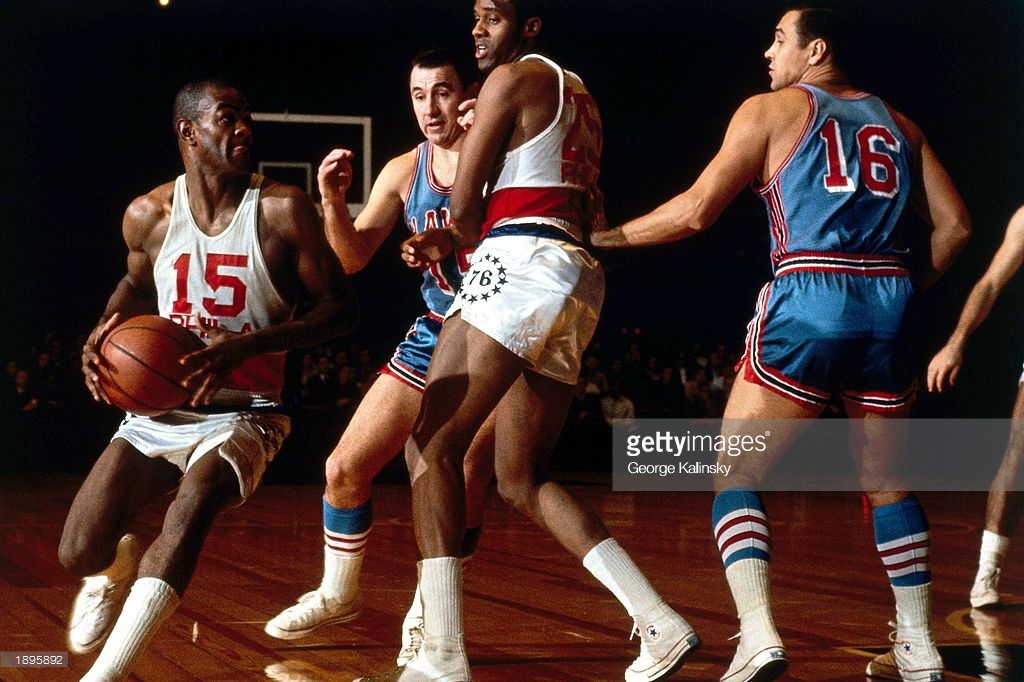

Hal and Wilt

This practice regimen also led Greer to adopt the unusual style of taking jumpers from the free throw line. “I figured I practiced my jumper all the time, so what was the difference?” he says. “And it worked– I shot 80 percent.”

Greer also shot 45 percent from the field, despite living almost completely outside the lane. “I could hit those jumpers with my eyes closed,” he says. “[Sixers coach] Alex Hannum used to say that he would rather me stop at the foul line and shoot than take it to the hoop, even on a breakaway!”

Despite all his accomplishments, Greer says that his proudest basketball moment was simply making the Nationals his rookie year. He was drafted in the second round of the 58 Draft after averaging 23.6 ppg as a senior and he insists that he kept his bag packed throughout rookie training camp, prepared to return to Huntington and follow his older brother into the police force.

“I had really planned on giving it my best and if I made it I made it and if not, the police force would be fine,” says Greer. “Nothing in my basketball career – including winning the title or getting into the Hall of Fame – was as great as just hearing I had made the team, I would have played my first year for nothing. As it went along, it became my business, but I loved the game so much.”

Greer almost immediately became a key contributor to a great team. Led by Schayes, center Red Kerr and pg Larry Costello, the Nationals took Boston to seven games in a thrilling, hard fought Eastern Finals, before falling 130-125 at the Boston Garden.

“That was the best team we had at Syracuse,” Schayes recalls. “Larry and Hal were a great backcourt and we would have won the championship if we could have gotten by Boston, who beat Minnesota 4-0 in the Finals.”

Instead, the Celtics won the first of eight consecutive titles, a streak not broken until Syracuse had long since moved to Philly and Wilt had come back to his hometown. Wilt’s arrival in the middle of the 64-65 season was a key step towards a title, but it was not necessarily easy for Greer to adjust to.

“Philly was Wilt’s hometown and once he arrived, he was the focus of everything and everybody,” recalls Chet “The Jet” Walker, another key contributor to those teams. “I think Hal sometimes felt he was being overlooked and underrated, because he had been the unquestioned star when we moved from Syracuse and became the 76ers and Hal was definitely the star. Despite his greatness, he had a certain insecurity inside him and he definitely felt under-appreciated at times, but he adjusted to Wilt’s style easily because he was such a smart player.”

Schayes, who was the coach when Wilt arrived, expresses similar thoughts, but Greer himself insists that he had no trouble adapting to the Big Dipper.

“I knew what kind of game he had from all the years playing against him and we all knew if we were open Wilt would give it to use because he was a great passer,” Greer says. “He was the main focus of the team and that was fine because you need a guy like that to win.”

The championship team came in the midst of Greer’s great, remarkably consistent career. Greer was named to the All-NBA second team seven straight times – only the presence of fellow Top 50 players Jerry West and Oscar Robertson kept him off the first team. Mention those names to him now and his first response and he lets out a little hoot, before exclaiming, “My arch rivals! I was always sort of the third guard behind those guys.”

If that sounds like bitterness, it is not. Greer call the Big O the best, most complete player ever and names him and West as the starting back court on his all-time team of people he played with or against, along with Bob Pettit, Wilt and Elgin Baylor. Greer made the All Star team for 10 straight years, from 61-70, during which years he never averaged less than 19.5 ppg, while topping 22 ppg seven times. He was the All-Star Game MVP in 68 when he set the record for most points scored in a quarter (19). When he retired in 73, he held the career record for most games played (1,122) and ranked in the top ten in points scored, field goals attempted (18,811 and made (8,504) and minutes played (39,788).

Greer also had a great career at Marshall and was an all American as a senior, but his legacy there far exceeds his on-court accomplishments. He was the first black to play for a major college team in West Virginia and his success helped ease the way for the integration all Southern sports.

“I was prepared to go to Elizabeth State Teacher’s College, where my brother had gone, when coach came up to me during a high school basketball game and asked if I wanted to play at Marshall. I was very surprised and a little scared but I felt I had to try to do this, because Jackie Robinson was one of my heroes. I knew I would have to endure some of what he went through.”

Today, nearly 50 years later, Greer is not eager to get specific about any of the racial harassment he faced. He says that his quiet nature lessened the attacks and fondly recalls being warmly welcomed to campus on his first day by several white former high school opponents.

“I had very few issues on campus and absolutely no problems with my teammates,” Greer says. “ I did have to endure a few incidents at away games, but the world had to go through that to get where we are now.”

Whatever pain Greer suffered in those days must have been somewhat soothed in 1966 when Huntington saluted its native son with a Hal Greer Day. Twelve years later he was honored by his hometown again when 16th street was renamed Hal Greer Boulevard “That was one of the greatest moments in my life,” he says. “The boulevard goes past my high school, my elementary school and Marshall University.”

Clearly, Greer’s status in his hometown is secure, but not so at the site of his greatest NBA triumphs, Philadelphia. Greer and the 76ers parted on bitter terms following the putrid 9-73 1972-73 season. As the franchise’s all-time leading scorer, he thought he deserved better than playing mop up minutes on the worst NBA team ever assembled.

“It was difficult, yes, and not just that season,” Greer says. “Unfortunately, I‘ve seen it happen so many times, but at the time I was devastated. I had spent all 15 years in the organization and had given them my whole life and to be treated like they did me was a little disappointing. I just

wanted to retire with dignity. Charles Barkley says all the time that’s all any athlete wants. But they had a new owner who was not a basketball man and a new general manager named Don DeJardin, who was a military man, and it was his way or the highway. Those last three or four years were tough for me.”

wanted to retire with dignity. Charles Barkley says all the time that’s all any athlete wants. But they had a new owner who was not a basketball man and a new general manager named Don DeJardin, who was a military man, and it was his way or the highway. Those last three or four years were tough for me.”

I mention that Sixers Ambassador World B Free has told me that the team would love to have Greer back to honor him again (his number was retired in 76) and he laughs, before saying he’s not interested. “I’ve heard that so many times and I’m not really open to that. Those days are over and I’m still trying to get the last three or four years there out of my system.”

According to some friends and former teammates, Greer was rebuffed in his attempt to get a post-playing job with the Sixers, who were upset that he had publicly aired his grievances. Greer remained in Philadelphia until the early 90s, when he lost his home and many of his most prized possessions, from wedding photos to basketball memorabalia due to financial difficulties.

“We went through a thing in Philadelphia where we had bad advice and bad information and someone came and took over our house and everything in it,” says Greer. “I got some stuff back, but a lot of important things like wedding presents were gone forever, though we still have the memories in our hearts. It was a very difficult and that’s when I left Philadelphia and vowed I would never go back. I’ve mellowed a little but I’m in Arizona now and I’m not looking back. I’m onto a new phase in my life, retired and playing as much golf as I possibly can. I have a 10 handicap and I’m aiming for single digits”

Greer gets a little testy for the one and only time when asked if the crushing blow of losing his house combined with his nasty break with the Sixers is what led him to retreat from public life.. “I haven’t gone anywhere, “ he says. “I’m just a quiet guy who likes to spend time at home with my family.”

Greer and Mayme, his wife of 39 years, have three kids. Their youngest, Cherie, is the president of Grant Hills’ GrantCo Enterprises, overseeing all his business deals and off-court ventures, as well as an All American lacrosse player, who has played in three World Cups, winning a gold medal each time and captaining the U.S. squad in ’01. She says that her father didn’t speak much about his basketball career when she was younger.

“I didn’t appreciate the scope of his achievements until I got older,” she says. “Now I’ve finally begun to understand how many obstacles he had to go through to make it. Most of it comes from people telling me how great my father was, watching the reaction of older folks, when they recognize him and listening to a lot of people’s stories.”

Of course, stories and word of mouth are all anyone has to remember those days by, for the most part. You won’t flip on ESPN Classic and see a Syracuse Nationals game any time soon. The tapes don’t even exist. As Jerry West notes, the little press that existed at the time focused on a handful of players, like himself and Wilt. It was easy for a quiet, shy, fiercely proud guy like Greer to slip under the radar.

“We didn’t have all the people promoting our game like we have today,” says West. “If we did, Hal would have been much better known, because his game was totally unique; he stands out because there’s no one to really compare him to. He could score, pass, defend, and he was totally serious and committed to winning, which you have to be in order to be great at this game. He was really a terrific player.”