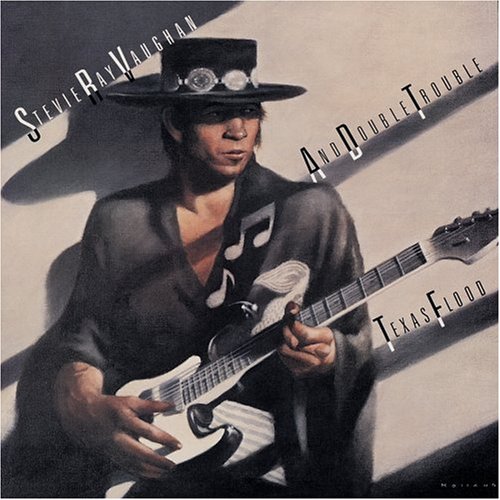

The Making of Texas Flood

In honor of Stevie Ray Vaughan’s birthday, the 30th anniversary of his debut recording and the release of a new version, Texas Flood (30th Anniversary Collection), I present the following story of the making of Texas Flood. This was written for and originally published in Mojo circa 2001.

In honor of Stevie Ray Vaughan’s birthday, the 30th anniversary of his debut recording and the release of a new version, Texas Flood (30th Anniversary Collection), I present the following story of the making of Texas Flood. This was written for and originally published in Mojo circa 2001.

When Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble were booked to play the 1982 Montreux Jazz Festival, it seemed that years of gigging and hard work had paid off. At last, the Texans who had spent years touring in a milk truck that leaked oil had gotten their break, becoming the first unsigned act to play the prestigious fest. It was a long way from the small clubs the trio played back home in Austin.

The booking came about thanks to the intervention of music industry big wig Jerry Wexler, who saw Vaughan and DT perform at a record release party for their former bandmate, singer Lou Ann Barton, and pledged to help. True to his word, Wexler had called his friend Claude Nobs, the Montreux promoter and helped secure them a slot. Vaughan and Double Trouble appeared on July 17, 1982, at the Montreux Casino amidst an evening of acoustic blues and the audience was less than impressed with their fiery, rocked-up show. Vaughan opened with Freddie King’s instrumental “Hide Away” and tore thorough staples-to-be like “Pride and Joy, “Texas Flood” and “Dirty Pool.”

Any blues fan today would give their eye’s tooth to witness this show. But the Montreux crowd, not expecting such a blistering assault on their evening and perhaps put off by Vaughan’s unabashed swagger and the simple fact that he was white, was les than enthusiastic. In fact, a good portion of the people present booed while the rest were oddly silent. The show can be seen in its entirety on the two-DVD set, Live At Montreux, 1982 & 1985 (which also includes the band’s triumphant return three years later, as superstars). Watching it now, it is impossible to fathom what the audience was thinking in their tepid-at-best reaction. It is not, however, hard to imagine the crushing disappointment Vaughan must have felt.

“Stevie was broken-hearted,” recalls bassist Tommy Shannon. “He turned around and said, ‘I don’t think we sounded that bad.’”

Adds drummer Chris Layton, “After the show we felt depressed and bewildered. We had come so far with such high expectations and the response was so bad.”

Photographer Darryl Pitt recalls rushing backstage to console Vaughan, only to find him slumped on a small road case, looking like he had “been hit by a sledgehammer.” The dejection did not last long, however. The band was sitting glumly around its tiny dressing room when a Festival employee stopped by and said that David Bowie was in the house and wanted to meet them all.

Photographer Darryl Pitt recalls rushing backstage to console Vaughan, only to find him slumped on a small road case, looking like he had “been hit by a sledgehammer.” The dejection did not last long, however. The band was sitting glumly around its tiny dressing room when a Festival employee stopped by and said that David Bowie was in the house and wanted to meet them all.

“We sort of went, ‘David Bowie who?’” recalls Layton with a laugh. “And the guy said, ‘You know, David Bowie.’”

Vaughan, Layton and Shannon headed for the Musician’s Bar downstairs, where they hung out and chatted with Bowie for hours. Vaughan was, of course, delighted with the attentions of Bowie, who would soon proclaim the Texan the best urban blues player he’d ever heard and proclaim that no guitar player had juiced him up so much since he saw Jeff Beck in the early 60s at a London club. But Bowie, too, was pleased that the guitar firebrand was paying so much attention to him. On the heels of Low, Heroes and Scary Monsters, Bowie was regarded as a rather fringe artist in America at the time. So it was that when the rock star asked the unknown guitar stud whether he would be interested in doing some recording, the singer was just as pleasantly surprised that the guitarist said yes as the guitarist was that the offer was made.

“I expected and would have understood a polite ‘Thanks but no thanks,’” Bowie writes in the liner notes for the Montreux DVD. “You can’t imagine how delighted I was when he accepted the offer on the spot and said he’d love to try out a new kind of record just for the experience.”

The following night, Vaughan and company were booked to play the same hotel bar. Jackson Browne, who had performed at the Fest earlier that night was doing an interview in his hotel room when several members of his band barged in bubbling with excitement, insisting that whatever Browne was doing, he had to stop it and get down to the bar right now. Following his bandmates downstairs, Browne was similarly awed by what he witnessed and soon climbed on stage.

Recalls Layton. “We played all night, with Jackson and his whole band sitting in. We jammed until seven a.m., and at the end of the night Jackson said that he had a studio in L.A. and we were welcome any time we wanted to come record some tracks free of charge.”

Over the next six months, the meetings with Browne and Bowie would launch the career of Vaughan and Double Trouble and change the course of blues guitar, bu that was far from clear when the band returned to Austin. They were poorer than a church mouse and their immediate prospects didn’t seem any more promising than they had for the past few years. Vaughan decided to take Browne up on his offer. The singer agreed to give the group 72 hours in Down Town over Thanksgiving weekend, 198, and they quickly booked a short tour to help cover their travel expenses. While most of the studio staff wanted nothing to do with helping some raggedy assed unknowns over a long holiday weekend, engineer Greg Ladanyi offered his services.

“We went in there, just hoping hoped that maybe we were making a demo that would actually be listened to by a real record company,” says Layton.

They were, in fact, recording their debut album, Texas Flood, though the circumstances hewed much more closely to their demo ideas.

“Down Town really was just a big warehouse with concrete floors and some rugs thrown down,” says Shannon. “We found a little corner, set up in a circle looking at and listening to each other and played like a live band.”

“We just rolled in there like it was a rehearsal or something and the guys working there were mildly annoyed because it was Thanksgiving weekend and they wanted to be home,” says Layton. “We were so unprepared, we were like, ‘Hey, uh, you guys got any tape?’”

Ladanyi offered up some used tape to record over, including some of the demos for Browne’s not-yet-released album Lawyers in Love. The trio basically just ran through a typical live set of their strongest tunes. Ladanyi was not interested in getting too deeply involved and the band was unsatisfied with their sound throughout the first day. Richard Mullen, a Texas musician and friend of the band who had been coming to their shows and running sound gratis, happened to be in town, recording with singer Christopher Cross. Not wanting to ruffle any feathers and grateful for the free time, Vaughan had not pushed when Browne and Ladanyi balked at having an outsider behind the console, but by the time they broke for dinner on the first night, the guitarist was vocally upset with his mates about the results. Mullen replied by urging the shy frontman to exert his will, saying in essence, “This is your shot and your show and if you want anything to be different, you have to speak up.”

Returning to the studio newly emboldened, they found that Ladanyi had left. In his place was an assistant, who did not think his job involved more than “pushing the stop and record and buttons.” So Mullen took over, tuned the drums and dialed up the sounds he wanted to hear on Vaughan and Shannon’s amps. He also employed some sound baffles between the players to decrease leakage and allow cleaner tracks of each instrument without forcing the band to physically separate and lose their live vibe. From then on, the band rolled through their repertoire, recording two songs that night and eight the following day. There is some dispute about whether Mullen appeared at the end of the first day or the beginning of the second and whether the whole session lasted two or three days. In any case, they definitely did record seven of the album’s eventual 10 tracks on a single day, November 24, 1982, when they also cut “Tin Pan Alley,” a blues classic that was an SRV standard and which appears on Sony’s 1999 remastered version of Texas Flood. Vaughan cut only scratch vocals, adding only these tracks back at Mullen’s Austin studio.

“That whole recording was just so pure; the whole experience couldn’t have been more innocent or naïve,” says Layton. “We were just playing. If we had known what was going to happen with it all, we might have screwed up. But we just went in there and did our live show. The magic was there and it came through on the tape.

“It’s funny, too, because people tell me all the time how much they love Stevie’s tone on that album and ask how he got it. It was so simple it’s ridiculous; he plugged his Strat into ‘Mother Dumble,’ a Dumble amp that Jackson owned and we found in the studio.”

THE ORIGINAL “TEXAS FLOOD” BY LARRY DAVIS:

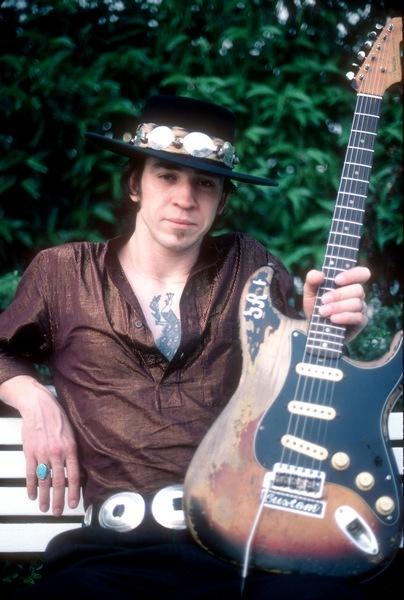

Vaughan’s hard-edged, vintage sound would soon turn the guitar world’s perception of tone on its head. At the time, rock music seemed eager to leave the past behind. Indeed, many thought guitars passé, with futurists proclaiming that the instrument would be permanently transformed by MIDI applications and replaced as rock’s dominant instrument by the synthesizer. Even many guitar loyalists thought the classic sounds were no longer adequate, transforming their instruments by running them through racks of elaborate, high-tech gear to create heavily processed sounds. Odd-shaped, brightly colored axes were all the rage.

Vaughan’s gear throughout his career was profoundly old school and never more so than on Texas Flood. Eventually, the tones he coaxed from his old but timeless gear would ignite a vintage craze that rages to this day and also launch a new market for small, high-end boutique amplifiers that replicated classic sounds with modern conveniences.

Following the recording sessions, the group stayed in LA to play several dates. On one of these nights, Layton was awakened at the Oakland Gardens Hotel by a three am phone call. “I answered in a fog and it was a guy with an English accent asking for Stevie,” Layton recalls. “I said that he was sleeping and asked who was calling. He goes, ‘It’s David Bowie and I’d like to speak to him now if possible. I got Stevie up and Bowie asked him if he wanted to come to New York and cut some tracks.”

Vaughan accepted the offer and flew to New York in the third week of December to join Bowie and producer Nile Rodgers at the Power Studio. Let’s Dance was complete except for lead guitar tracks. Vaughan’s performances, Bowie has said, “ripped up everything everyone thought about dance records.” Vaughan had casually become the linchpin in birthing a sound that Bowie had long heard in his head – a new kind of dance music that combined Euro sensibility with raw American blues power. Blown away, Bowie quickly asked Vaughan to join his touring band and the offer was accepted, though not without some real angst about leaving behind his own group.

“Stevie‘s plan was to do it for a year, take the money and pay us to keep the band together,” Shannon says.

As rehearsals continued in Dallas, then New York, Bowie and his band grew increasingly excited about the sound they were crafting around Vaughan’s blistering lead work and anticipation rose for bringing this heady brew around the world.. It was not to be, however.

What happened next is not entirely clear. Bowie says that as the band was literally loading onto a bus to go to the airport and fly to Europe and commence touring, Vaughan’s manager demanded a much higher salary or else the guitarist would not tour. The offer was promptly rejected, leaving the guitarist and his bags stranded on the sidewalk as the bus pulled away without him. Layton and Shannon have different recollections of the event. They say that Vaughan, already uncomfortable in a sideman’s role and upset that several promises about opening some shows himself were broken, finally snapped when told that he couldn’t mention his own band or music in interviews.

“He just couldn’t do it because it wasn’t what he loved playing,” Shannon says. “He liked David and his music, but it wasn’t where he was headed and Stevie could not do what he didn’t love.”

Whatever the exact circumstances, Vaughan most definitely did quit Bowie on the eve of a huge world tour to return to Double Trouble and their oil-leaking milk truck.

“I really wasn’t surprised when Stevie quit, but I sure was happy,” recalls Layton. “I couldn’t believe that just when we seemed to have all this momentum, Stevie was going to be gone for at least a year, maybe more. We really thought it might be over, right when we had worked so hard to get to that point, where it seemed like something was going to happen.”

Something was, in fact, already happening. Urged on by Layton and Shannon, who were feeling increasingly desperate that their moment was passing, manager Chesley Millikin had been shopping the 10-song tape made at Browne’s studio and found an admirer in John Hammond. The septuagenarian A&R man, whose discoveries and signings included Billie Holliday, Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen, took the tapes to Epic and essentially demanded they sign him. Just like that, and with little other label interest, Vaughan quickly had a deal with Epic Records.

“Epic wanted to release our demo right away and we got more attention because people wanted to know who this unknown guy who told David Bowie to take a hike was,” says Layton.

Vaughan’s pungent playing on Let’s Dance, redolent of Albert King, garnered attention as well, from fans and fellow musicians alike.

“I was driving and ‘Let’s Dance’ came on the radio,” recalls Eric Clapton. “I stopped my car and said, ‘I have to know who this guitar player is today. Not tomorrow, but today.’ That has only happened to me three or four times ever, and probably not for anyone in between Duane Allman and Stevie.”

With Hammond on board as Executive Producer, Vaughan cut new vocals for “I’m Cryin’” before the album was mixed at New York’s Media Sound and released on June 13, 1983.

“We started touring behind Texas Flood and we could feel things changing, the crowds slowly getting bigger and bigger,” says Shannon. “Then we got rid of the milk truck and got a bus and we were in heaven — even though it was a really shitty bus.”

Adds Layton, “We toured the whole country, playing every night, selling out 500 seat clubs, with 200 people standing outside trying to get in. We could feel this incredible momentum building.”

“What really brought it all home for me was when we played at the Palace in Hollywood,” adds Shannon. “We had played there before to mediocre crowds and this time there was a line stretching down the street and around the corner.” (Three songs from the September 23, 1983, performance at the Palace are featured on the remastered Texas Flood.)

Proof that Vaughan was entering the music mainstream came when the album was nominated for two Grammys: Best Traditional Blues Recording and Best Rock Instrumental Performance (for “Rude Mood”). The band also appeared on the Austin City Limits television show and Vaughan won three categories in Guitar Player magazine’s Readers Poll: “Best New Talent”, “Best Blues Album”, and “Best Electric Blues Guitarist,” an award he would win every year until his death. MTV was still fairly new and quite wide open and they began playing the video for “Pride and Joy.” In retrospect, given the strength of the album, all this success seems obvious, but in 1983, it was anything but. A reasonable betting man would have wagered his house that Vaughan and his old school blues-rock trio would fail to register on the popular culture’s radar screen. But the 29-year-old guitar firebrand was clearly playing by his own set of rules. “He was a leader, not a follower,” notes B.B. King “and you didn’t have to be a guitar expert to know that.”

Texas Flood blew open the locked doors of popular music and proclaimed that blues could be a potent commercial force. The album, combined with the runaway success of Let’s Dance, not only put the unknown Texan on the map but also signaled that uncompromised, from-the-gut guitar music was not dead as a commercial and artistic force.

“Stevie Ray Vaughan single-handedly brought guitar- and blues-oriented music back to the marketplace,” recalls Dickey Betts, whose Allman Brothers Band were prominent casualties of the era’s anti-roots disease. “He was just so good and strong that he would not be denied. When I heard ‘Pride and Joy’ on the radio, I said ‘Hallelujah.’”

Vaughan’s dramatic arrival not only helped smooth the way for the return of classic blues-oriented rock acts like the Allman Brothers, but it also made the environment more hospitable for his own peers, including The Fabulous Thunderbirds (featuring big brother Jimmie Vaughan), Robert Cray, and Los Lobos, all of whom had hits in the years following Texas Flood. Stevie also shone a bright spotlight back on his original heroes, most of whom had been languishing — overlooked and usually sans record deal. Albert King, Buddy Guy, Lonnie Mack, Hubert Sumlin, Otis Rush and Albert Collins suddenly found themselves once again being hailed as guitar titans, with interest in their music skyrocketing to levels unseen since the white rock audience’s initial discovery of blues in the 1960’s.

Certainly, as he himself pointed out, Vaughan owed a huge debt to these originators, but his music was not simply derivative; he hungrily swallowed his influences, fully digested them and crafted a style uniquely his own. In so doing, he succeeded where countless others had failed — reinventing the blues in a manner both visionary and true to the original material. It was a goal shared by every hippie with a Muddy Waters record but accomplished by precious few.

“Stevie’s playing just flowed,” says B.B. King. “He never had to stop to think. His execution was flawless, and his feel was impeccable. Stevie could play as fast as anyone, but he never lost that feel.”

Adds Bonnie Raitt, a longtime friend of Vaughan’s, “Just when you thought there wasn’t any other way to make this stuff your own, he came along and blew that theory to bits. Soul is an overused word, but the fire and passion with which he invested everything he touched was just astounding, as was the way in which he synthesized his influences and turned them into something so fiercely personal.”

The word about Vaughan was out on the blues circuit for years, Raitt adds. Guy, King, Dr. John and others who passed through Austin had long been telling her about this kid who “was just killing it.” With the release of Texas Flood, the rest of the world got hipped as well.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!